Winter at Blame Cannon invites you to enjoy a rotation of stories about global warming in prehistoric times, stories of memorable departures in my life, and stories about coal:

Coal #1. How coal use transformed cooking, cleaning, and domestic roles.

Coal #2. How coal mining and the excavations for canals to transport coal proved stratigraphy, creating the data set for seriously thinking about deep time.

Today is Coal #3. The Train.

Waiting for a Train

I’ve read so many claims about the transformative power of this or that technology. In just the last week I’ve seen articles declaring the shattering importance of the telegraph, the smart phone, and of course always the internet. (Back in its early days I remember tech bros avowing the internet the most transformative invention since fire.) Last year Artificial Intelligence.

One of the intellectual founders of the modern world, Francis Bacon, got the ball rolling by back in 1620, declaring the importance of printing, gunpowder, and the magnetic compass.1

And it is well to observe the force and virtue and consequences of discoveries; and these are to be seen nowhere more conspicuously than in those three which were unknown to the ancients, and of which the origin, though recent, is obscure and inglorious; namely, printing, gunpowder, and the magnet. For these three have changed the whole face and state of things throughout the world.23

There’s a lot of truth in this, but it hasn’t been a good influence. Technology just doesn’t transform human existence in the manner of a sudden mutation in a sci-fi movie. Iron weapons long coexisted with bronze. Life before flip phones or microwaves wasn’t that different. Even gunpowder, printing, and the compass—which did radically change the world—took many centuries to make their mark. Early guns never won a battle; compasses were useless without compass-friendly maps; and it’s not clear the printing press would have even turned a profit without the humanist revolution in education and culture. Moreover, note that gunpowder, printing, and the compass did not rapidly transform China, where they originated—so claims that technological changes drive cultural changes are usually overstated.

As we’ve been seeing coal did change everything, but coal wasn’t a technology, much less a new one. It’s a fuel burned since prehistoric times, and not burned very much for reasons we visited in Part I.4

Yet there has been one invention that does live up to the hype:

This week let’s talk about the railroad, i.e. the train, the iron horse, the locomotive, the steel rails, the choo choo.

By “railroad” we mean a technological package of locomotives pulling cars over metal rails on wooden cross ties. This package went from prototypes to mass production in only about a generation, involved the contributions of probably fewer than a hundred major inventors, and transformed every square of the earth that it reached. (And there isn’t much of the earth that it hasn’t at least tried to reach.)

The Ballad of John Henry

Railroads descended from roads of wooden planks with wooden guide rails. If a cart is moving over the same route repeatedly—like a hopper cart in a mine—it’s smart to build a track for it to run on. Coal mines used a lot of these sorts of tracks to trundle hoppers of coal to the surface. Then as we saw in Part II, as coal production increased versions of these “rail roads” were extended to canals or ports so wagons could haul coal to market more quickly and efficiently, running back and forth pulled by oxen or horses. The huge volume of coal made all this profitable.5

Since wooden rails wear out, however, there were various attempts to sheathe or replace the rails with metal, eventually settling on new commercially-produced wrought iron (which was created in a process involving coal too).

Next came replacing the horses or oxen with steam engines. Steam engines were already familiar to the coal industry because they were used to pump water out of the mines. That’s what they’d been invented for.6

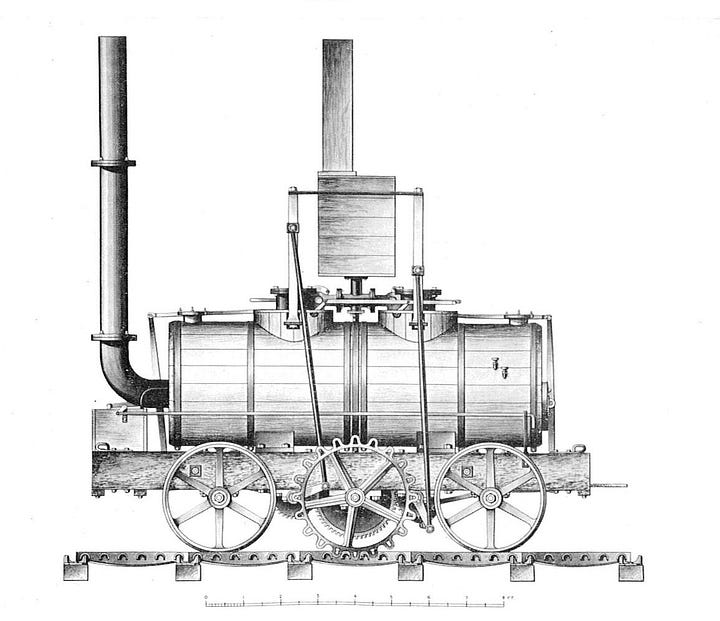

Getting the right mix of durability, power, and affordability to bring the tracks and trains together took tinkering. In the first decades of the 1800s there were various steam trains in Britain and the U.S. (which aped British technology) some profitable, some not, looking often like steampunk fantasies, but all contributing to ideas and learned lessons. (Wikipedia has several articles naming the people, places, and steps. You can start here.)

By 1830 in Britain and America, in Germany soon after, and by 1840 in France and Russia the achetypal train appears. Engine, coal car, passenger cars, box cars, baggage cars, and caboose on cross-tied rails as portrayed in folk songs, model train layouts, and Thomas & Friends cartoons. This suite of technology spread over the planet earth. For a century train whistles cried through the rural nights and urban days, piston-churned wheels inspired fiddle tunes and harmonica riffs, and railroad timetables and pocket-watch-snapping conductors ordered civilization.

Casey Jones

Before railroads the only large-scale transportation was by water: boats, barges, or ships over rivers, lakes, seas, and canals. Land travel works fine for small stuff like spices, gold, frankincense, or myrrh, or a few travelers bumping along in a stagecoach, but heavier loads of people or stuff over longer distances gets logistically very difficult, and thus very expensive.7

So trade cities in the ancient or medieval world clung to shores and wharfs, and cities that didn’t start on a coast quickly built walls to the nearest port. Civilizations tended to hover in the warmer regions where waterways didn’t freeze over. The Romans famously did build roads, and other empires did as well, but these were to move troops and messages, not to haul grain. Inland rural villages and towns fed themselves or in times of famine were abandoned.8

So railroads worked like inland canals, but were much cheaper to build.9 And didn’t have to follow shipping routes, so trade became less like arteries branching into the interior, and more like a grid moving in all directions.

Wreck of the Old 97

Inland towns and cities suddenly could become as consumer-oriented as ancient coastal towns had been, and this increased the total number of markets, so that the economy could become more industrial, commercial, and interconnected. Specialization became less based on local resources and more on local effort, strategies, and investments. Investment money—capital—could start companies anywhere with railroad access and compete with other companies anywhere else.

The industrial revolution calls to mind a new type of cheaper factory-produced stuff, machine-made clothing, machine-made tools, and so on. That’s part of it. Replacing human, animal, and water power with steam engines is another part of it. But without railroads the market for all those new industrial goods would be restricted to canals, navigable rivers, and coasts. With railroads markets were everywhere in all directions.

One interesting aspect of all trade is how consumers can use something without knowing where it really came from or how it’s made. A hunting band can use traded obsidian or amber even if they don’t know where it comes from. This becomes even more true of luxury goods like silk or certain spices, which were often a mystery in historical times; not just where they originated but how they were processed into the form being sold. Railroads vastly increased the number of people who could live this way. Life was filled with strange wonders of unknown origin. Magazines from somewhere else, created who-knows-how contained advertisements (which were created how?) extolled the virtues of this or that manufactured product. This continues to our own time: most of us do not know how most of the stuff around us is made or works. Trains didn’t start this, but they vastly expanded it

If railroads reduced knowledge and interest in how stuff is made, they certainly increased knowledge and interest in other places. Railroads offered ordinary humans a chance to travel without having their own horses (which is very expensive), rely on rented horses such as in a stage coach (fairly expensive plus inns), or walk. And the train was much faster than roads and canals. A citizen of Charlottesville, Virginia, once the railroad reached here in 1850, could travel to Richmond in 5 hours rather than 3 days. Before the railroad only the wealthiest class of English could travel Europe; after the railroad the middle class could as well.

Wabash Cannonball

Governments have always had strategic interest in transportation, if only for armies, mail, and tax collectors. National elected governments such as the British parliament or the new American state and federal legislators added commercial interests in transportation. So these national governments loved railroads. Railroads were cheap enough to build that, unlike canals, government funding wasn’t critical, so a politician could make money by investing in railroad stock while spared any guilt about the treasury balance.

Railroads, however, did require government intervention. A planned route was no good unless all the property was available. Otherwise as a route was extended speculators could anticipate where it was headed, buy up property near the destination, and refuse to sell for a reasonable cost.10 So governments expanded eminent domain to secure the properties needed, and this was a major increase in government power. To be sure governments had long done this for canals and roads, so the process wasn’t new, but there were a lot more railroads than there had ever been canals or roads. The process could become very corrupt as towns, private speculators, and the railroads themselves vied to game it all. The rapid western expansion of American railroads particularly often operated like a Ponzi scheme with winners and losers.

Chattanooga Choo Choo

Speaking of the west, the iconography might be dominated by the lone cowboy, the saloon, or the tumbleweed drifting across a dusty street, but the west became the West because of railroads. The massive grain farming of the midwest or the cattle ranching of the far west wouldn’t have been possible without railroads to transport the product.

Consumerism, the satanic mills, armies and victims in boxcars, and stealing of western land from its indigenous inhabitants, the European colonial empires seizing the world, government corruption—all that is intimately tied to railroads.

Any thinking person could have doubts about whether the trains were a good idea after all. Wouldn’t we have been better off without them?

I’ve pondered this a lot, but it seems to me, this guilt-by-association of everything in the past is an aspect of the nihilism that haunts our times, at least in the U.S. It’s a vestige of our lack of actual democratic experience and participation in the world. Yes, we vote on candidates for office, but our actual government has hardly any actual democratic components left beyond that. Our elected officials aren’t responsive to public opinion, the bureaucracy isn’t responsive to public opinion, and activists and pressure groups aren’t responsive to public opinion. Voting and calling senators may give us influence, but we don’t have any power. Trump, Musk, Israel—we just don’t seem to have any say. So it’s tempting to condemn everything that got us to this point or remind us of this point or believe it’s always been this way. But imagine, instead, that we had deliberative assemblies and that these assemblies were large enough and had enough authority that we all would have a decent chance of serving in one. Picture making motions, giving speeches, voting as one of a group small enough that our votes would matter, but large enough not to be like a bureaucratic board meeting. Imagine approving policies from that truly democratic, rule-by-the-majority viewpoint. Many towns might choose not to have factories or coal plants, or even cell phones, but every town would want a train station. If we were actually responsible for rebuilding the world from scratch, I’ll bet we were build more trains, not fewer.

Trains mean opportunities, freedom, and communication, and unlike airports and roads, they actually pay for themselves. Of all that came out of the industrial revolution, I just don’t see much downside to trains. And if our current civilization collapses—probably because we can no longer afford widespread automobile use—I can imagine smart phones, streaming, and the internet collapsing too, but even in a worse case scenario, trains will survive, and probably make a comeback.

Trolley Song

The railroad allowed the import of enough food and export of profitable commercial products for new larger metropolitan cities. London reached 2 million about 1850, and New York reached 3 million in the late 1890s. These huge cities did not take population from smaller cities as huge cities seem to in our automobile-based world. Instead, all railroad-connected towns and cities seem to have increased in size, dynamism, and wealth during the railroad age. Only if the railroad moved elsewhere would a town die. Trains brought the Sears kits that were used for building homes, and later as a city grew, trains brought in the bricks that were used for replacing the homes with apartment buildings.

What made it possible for individual cities to grow was a more intense settlement pattern, and that encouraged and was encouraged by public transportation. From the mid-19th century cities were experimenting with subways, elevated trains, and streetcars. Like heavier rail, streetcars were originally pulled by horses, but here it was electric engines that eventually replaced the animals.

Now it wasn’t just the transport networks allowing mail to reach small towns and rural areas that increased the readership of newspapers and magazines and new mass-market novels; commuter and intra-city trolleys and trains dramatically increased daily reading. Instead of walking to work, a commuter rode to work, reading on the way. To lure these readers newspaper editors and publishers were particularly adept at innovating with star reporters, feature writers, comics, columnists, and reviewers.

Speaking of reviewers reliable train service meant that performers could tour more easly and profitably. While the big-tent circuses that toured rural areas might be more famous, it was the urban Vaudeville circuit that trained whole the generations of performers that performed on Broadway, the nascent cinema, and later on television.

What’s especially interesting about rail travel is how much it impacted popular music. Although trains are major elements of a few novels (Middlemarch, Murder on the Orient Express, Dombey and Son11), mostly like horses in earlier novels trains are in the background moving the characters around. Where trains really made their mark—far more than horses, cars, and planes—is in popular music.

In fact, all of the subheadings of this post are popular rail songs. (Click on them!) I could have linked to dozens more.

Take the A Train

For a moment instead of picturing the economy as money or credit or capital or products, picture the economy as energy: At first it’s human energy expended to hunt and gather but exploiting, say, the stored-up energy in wood to make a fire, and much later the energy of domesticated dogs to help with hunting. Much later humans exploited animal energy, horses, oxen, and in a sense all domesticated animals. And that’s where things stayed for thousands of years.

Coal was the first widely distributed fossil fuel (Oil and natural gas would follow), and coal is stored-up energy from eons ago. There’s a massive supply of it. We’ll revisit this in a few weeks when we see how coal gave us modern economics.

But for today picture how primordial energy locked in black chunks can be dug up, transported, and burned today at a fraction of the effort needed to grow, chop, haul, and burn wood. Cheaper energy means cheaper everything.

Railroads were a vast multiplier distributing this coal directly, but also distributing the output of the factories that ran on coal, providing those factories with raw materials, intensifying the settlements of the people who worked at those factories, and providing those people with entertainment, transportation, and communication.

City of New Orleans

Railroads are one of those rare innovations—like fire, the bow-and-arrow, and woven cloth—that just doesn’t have much of a downside. Yes, coal smoke is dirty, but a train doesn’t create anything like the smoke of a factory, and since so much is transported on a single train, the pollution is less than the same stuff being transported by cars and trucks.

In the late 19th century petroleum began to supercede oil, originally as a cheaper replacement for coal oil. Petroleum is an more concentrated and versatile form of energy than coal, but also has a lot more drawbacks. Picture human communities as sand castles lifed and increased whenever railroads reached them, and then being pulled down and apart a century later when automobiles arrived. We’ll take this up in a future post.

Thanks for reading Blame Cannon! Next week we’ll use some of the tools of archeology to look back on the prehistoric climate change.

Please subscribe and share!

Comments are welcome but please no profanity or personal insults!

I vaguely remember that he got his idea from Macchievelli but if so I can’t find where.

Novum Organum, Book I, CXXIX. But the origins of these three while obscure and inglorious to Bacon are known today to all be from China.

Speaking of Bacon, the basic form of writing we’re taught in American schools is the essay, a creation of the French writer Montaigne and introduced into English language by Francis Bacon. Today we’re taught a particular kind of essay. The student must state a thesis and defend it with evidence, usually written in response to some work of literature but sometimes some historical period. Often the more shocking the thesis, the better the grade—so long as the writer crams in the evidence. Far more than any technological breakthrough this writing form—bursts of opinion supported by cherry-picked evidence—is the basis of our intellectual culture. That’s where the internet really comes from if you ask me.

And we’ll come back to this. Believe that!

Hauling grain this way wouldn’t make sense since the source of the grain was so difussed, and hauling metals this way wouldn’t make sense because it was much less volume. Fish and salt were ancient products that were hauled in high volume from central points but of course they could be hauled by water. By the way, wood roads were not so unusual in past centuries. Syracuse, NY had a famous wooden turnpike in the mid-19th century.

The principle of steam engines was familiar to the ancient world, and some may have been built, but practical and durable steam engines were first developed to pump water in coal mines. The proximity to an endless fuel supply made this smart.

I’ve heard calculations that water travel is 12x more efficient than land travel, and railroads 6x more efficient, but I can’t vouch for those figures.

Colonial Virginia was somewhat unique in developing roads. The economy was based on exporting tobacco, so the roads were created for and created by heavy hogsheads of tobacco rolling along. Of course, Virginian towns were quite small.

Laying a railroad was considerably cheaper than digging a canal and as the tracks were laid—unlike a canal—the materials and equipment could be brought over the previous section to build the next section. A road had to be used to build a canal, but railroads could be used to build more railroads.

One of the most ridiculous aspects of Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged and it’s view of heroic capitalism is the pretext that anyone could build roads or railroads without the government.

Dombey and Son is by Charles Dickets allegedly focused on the train according to Google. I’ve never read it or seen any movie adaption.