Television media depends on print media and print media disappeared.

A bonus post, pausing from the Welcome to Charlottesville series.

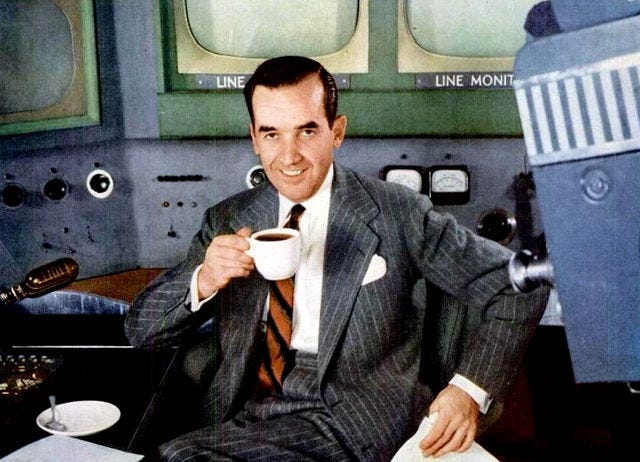

It’s presidential election time so the poor quality of American media is going to be more obvious than usual, evoking many complaints and many a wistful comparison to the days of news anchors like Walter Cronkite and Edward R. Murrow, who were trusted to tell the truth. Of course those guys in suits from back in the day weren’t always so great in reality, but they did present a higher-quality, more truthful product than we have today. Why? Because they read newspapers. TV journalists back then piggybacked on print journalists.1

The print journalists—especially multiple daily newspapers—formed the overall understanding of issues. They filled the sea on which star TV anchors sailed. TV people read the big-city newspapers, and the editors and reporters of big city newspapers read the smaller city newspapers. That’s how info was spread around the country. Print is a much better way of sharing ideas than any sort of video. It can expand passages where it needs to, it can use graphs and lists, and the reader can stop and reread passages that are confusing. Television and movies can be informative, even revelatory but they don’t convey information like writing.2

As of 20024 daily newspapers are dying and those that still survive have little local reporting, so when it comes to understanding the county in many ways the TV media is flying blind. So the problem isn’t so much bias, it’s ignorance. Take the presidential election:

Democrats probably can’t win without Michigan and can’t win Michigan without a decent turnout of Muslim voters. Many of those voters have really hated President Biden’s unconditional support for Israel in the Gaza War. It’s not clear if those voters will be motivated to come out for Harris. Without lots of local newspaper reporters with ties to those communities, it’s hard to get a picture of how deep or widespread those feelings are. Everyone who claims to know is basically conning themselves or us. Pollsters can’t help that much if they don’t know how to phrase questions or create samples.

Donald Trump and Kamala Harris are basically tied in Pennsylvania. Without lots of local newspapers with ears to the ground, it’s hard to get a sense of which voters will actually vote and what they really care about. Again, polls and focus groups are only as effective as the phrasing of the questions and sampling of the respondents. Without informed local eyes and ears, it’s all shots in the dark.

Or take a non-election question (though it probably should be an election question):

We have a huge homeless population in Charlottesville right now. How widespread is homelessness in other towns and cities? Are most of the homeless transient or local in origin? How does homelessness relate to drug and mental illness? We need newspapers to answer these kinds of questions.

To figure out why newspapers are dying it’s helpful to see where they came from.

I. Newspapers: the early centuries

Newspapers originally were side-effects of the printing press. Guttenberg developed moveable type in mid-fifteenth century Europe, and he and his imitators set up print shops to print bibles and classic Latin texts. They’d make a few extra guilders, ducats, or shillings by printing popular books and poems, calendars, pamphlets, account books, etchings, and eventually hand bills and posters for business advertising. A print shop then–and for centuries after–was a mix of modern bookstore, stationary shop, office supply store, publishing house, and copy shop all rolled into one.

So printers found they could sell sheets of local news, announcements, and ads that in the 1600s came to be called ‘newspapers’. The first ‘correspondents’ were letter writers corresponding from somewhere far-off with descriptions and reports of events.

Newspapers as part of a print business was a stable way to make a living for almost three centuries. If you were a printer in 1720 moving to a city in colonial North America, you’d bring your press and your set of moveable type, open a shop, print some books and pamphlets, try to drum up advertising business, and publicize it all–and yourself–by issuing a weekly newspaper. For a weekly you could deliver by mail, by hand, or sell out of your shop or a few friendly businesses, but those methods couldn’t usually distribute enough copies to justify a daily outside of very large cities.

The cost of type-setting and hand-pressing each page meant publishers couldn’t sell newspapers for less than about $1.50 an issue in modern dollars.

II. How did newspapers become a big deal?

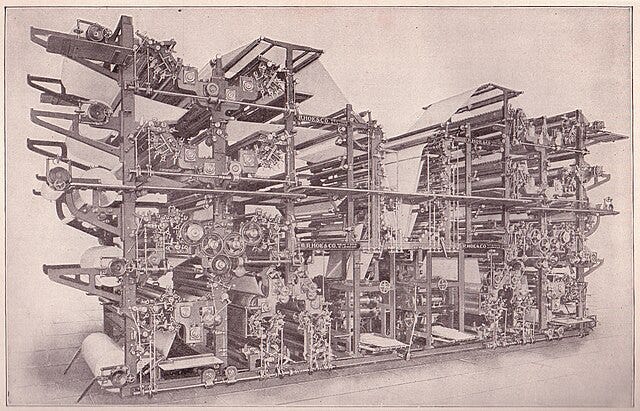

In the late 19th century presses got rigged to steam power so pages could be printed more cheaply. (Although the old hand presses persisted in small towns throughout the 19th century.) Printers also came up with faster and cheaper typesetting methods (I don’t know much about this but it also had to do with standardized machine production.), and more affordable methods of printing etchings and eventually color-etchings, and photographs.

Telegraphs allowed news to be sent from city to city. ‘Wire services’ could thus contribute content to multiple newspapers in multiple cities at once. This offered a way for local newspapers to announce national news.

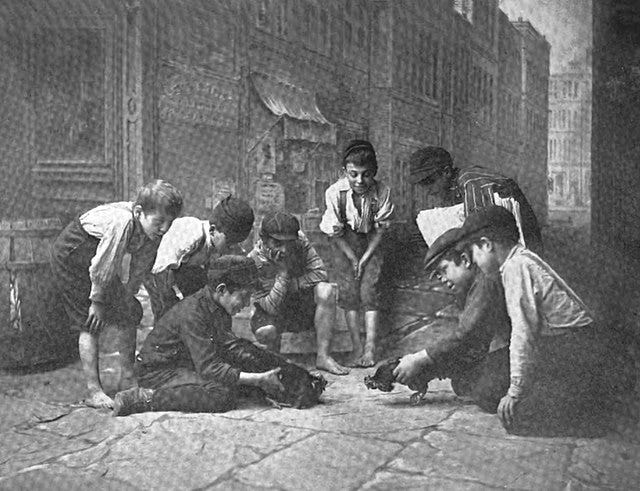

But what brought all this together was the growing populations of industrial-age cities. These urban megapolises had huge potential readerships in concentrated areas. This made daily distribution viable. You could print a lot of papers, drop bundles of them at ‘newstands’ or with ‘newsboys’ and they’d distribute them for you. Moreover, the increase in public transportation (omnibuses, trolleys, trains, and subways) gave the public a platform for newspaper consumption. People could pick up a paper (or 2 or 3), hop on a trolley, and read on the way to work, much as people on subways or buses today read their phones. Using the telegraph and this urban distribution network breaking news—like the winner of an election or news of a natural disaster—could be shared hours after it happened with those ‘Extra Extra! Read all about it!’ special editions hawked by shouting newsies in old movies. For the first time news could really be new.

Gals Named Nellie Bly

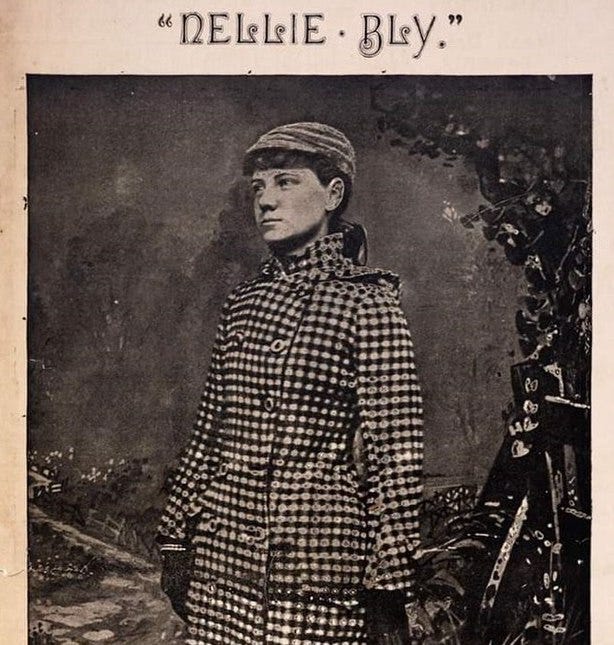

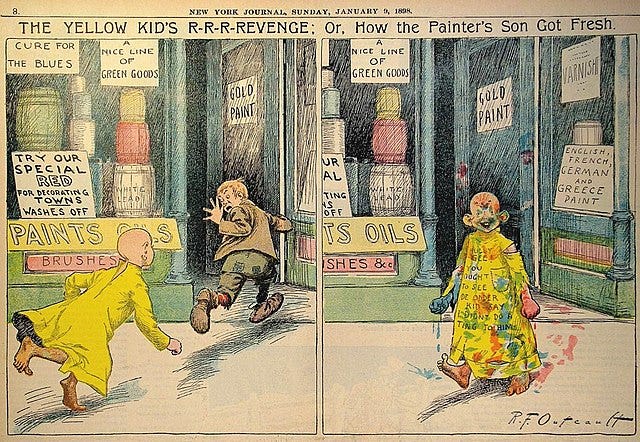

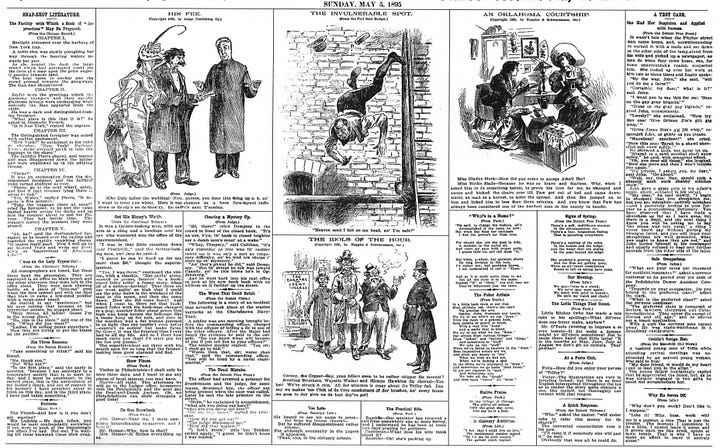

Starting around 1880 publishers like Joseph Pulitzer embraced these opportunities by hiring and promoting specialized talent of all kinds, experimenting with—inventing really—undercover reporters, investigative reporters, gossip columnists, opinion columnists, humorous columnists, theater and book reviewers, comic strip artists, and many other types of jobs that we take for granted today. Newspapers promoted their workers from within or hired from rival newspapers in the same city, giving these new ‘journalists’ a chance to develop ‘beats’–areas of expertise and sources. Competition between newspapers gave that talent bargaining power to gain decent wages.3

Recipes, fashion reports, advice columns, poetry, quizzes, and astrology shared pages with court dockets, department store ads, personals, estate sale announcements, obituaries, sports scores, opinions, play reviews, movie listings, cartoons, comics, and of course political news. Mostly importantly, newspapers promoted their own talent. A star reporter was featured as much as whatever or whomever the star reporter was reporting on. The reader was picking up familiar faces, characters, voices, and points of view.

A newspaper was a social club, marketplace, and event rolled into one. I think of the Roger-Kanners-Prince song sung by Louis Armstrong, I Guess I’ll Get the Papers and Go Home. The singer picks up the papers–plural–to read the way we might binge-watch Netflix.

III. Why did newspapers die?

This new model of daily papers worked for about a hundred years. But below the surface the pressures were building. Television, automobiles, and suburbanization halted per capita growth and should have been canaries in the coal mine, but growth in population and education levels actually kept total newspaper circulation on a slight upswing. About 1970 things leveled off. Per capita readership began to decline—a louder canary—but the decline was balanced by population growth.4

So from 1970-1990, like much else in America, on the surface thing were fine. Meanwhile the structural issues of the post-war period were unresolved:

The suburbs. Distributing daily newspapers to individual houses in the growing suburbs was much more challenging than dropping bundles with newsies and newsstands. The U.S. Post Office couldn’t possibly manage it. So publishers had created entirely new distribution systems with trucks, fuel, and labor. That is inherently expensive, but especially after the 1970s when the US shifted from oil exporter to importer.

Television. Kennedy getting shot, astronauts landing on the moon—meant everyone turned on their TVs. Those old ‘extras’ for big events were too slow and weren’t affordable to distribute in the suburbs.

Debt. Much like other American businesses newspapers had been buying up one another from the beginning. In good times publishers wanted to increase profits. In bad times distressed publishers wanted to avoid bankruptcy. Publishers bought out other publishers often with the hope that centralized news gathering and shared features would reduce costs. Often they would buy up rivals, consolidate staff, and shut them down.

One symptom of all this was the gradual, steady increase in local monopolies. In the 1920s 500 U.S. cities had competing daily newspapers; by the 1990s only 10 did.5

Suburbs, television, and debt hollowed out newspapers from within, but daily papers stayed profitable by increasingly relying on wire services to provide content; cutting reporters and other local contributors; and most of all, doubling advertising rates.6

Newspapers could double advertising rates because every business needed to advertise in print; legal notifications had to be in print; obituaries and marriage announcements were traditionally in print; and most Americans relied on newspaper classified ads to find jobs or apartments.

Collapse!

Newspapers began their downward arc in the 1990s and this became a Wile E Coyote cliff plummet in early 2000s. Depending on monopoly status for revenues was always fragile, and when free monthlies and the internet offered new ways to advertise apartments or hire someone everyone realized that print ads were overpriced.

Maybe also there was politics. I’ve never seen this seriously studied so I don’t know how widespread it was, but I stopped reading my local newspapers (Daily Progress and Washington Post) because they both uncritically supported the Iraq War. (The story of how I realized the Iraq War was a bad idea is for another time; I’d never been right about anything before that and I wasn’t particularly informed.) Almost all the newspapers in the U.S. uncritically supported that war.7 Maybe that drove people to the internet.

Losing ad sales may have doomed most suburban dailies, no matter what, but it seems like they didn’t even put up a fight. But they could have. Pulitzer built his brand not on advertising but by hawking his product to readers.

It doesn’t seem like journalism as a profession approves of the P.T. Barnum skill of figuring out what the people want to see or read and getting it to them.8 Basically creating ‘stars.’ Two of the few media growth industries right now are YouTube and Substack and both of those work the same way Pulitzer did. Find appealing stuff and promote the people who are doing it.

The Future

What’s the future of newspapers?

Daily newspapers are dead. With people now having developed the habit of reading smart phones, I don’t see how any daily newspaper is going to survive. Older people will read them but distribution to the suburbs is expensive and that demographic will shrink. Plus TV can do breaking news better.

Some daily newspapers will go online. But they won’t really be ‘daily’; they’ll be news aggregator sites with their own original reporting. They’ll post breaking news whenever they have it. That’s how the successful online ‘newspapers’ already work. I don’t understand the internet well enough to know how far this model can be monetized.9 In any case this isn’t good for smaller local markets. Why should I read wire service reports of national news on my local website when I can read it on a national news site?

Weeklies can survive. People like to read, so there will come publishers and editors who figure out how to do what Joseph Pulitzer did a century and a half ago—put together stuff that people want to read, reports, essays, comics, poems—who knows?! I read great stuff on Substack every day. I would happily read the same writing in newsprint instead of on computer screens if that’s where the stuff I wanted to read was available.

Meanwhile the lack of active, well-funded daily newspapers presents a problem for the type of post-war professional government cities have come to rely on. (That’s why I’ve inserted this little tangent.) Professionalizing had real advantages, but it depends on an adversarial press. Without we need to rethink city governments. One answer is larger public assemblies, such as a city council of 12 or 18, so there are more likely to be members with a wide variety of knowledge bases, perspectives, and self-interests. But we’ll take that up down the road.

Meanwhile, speaking of information why not subscribe or share?

We’ll be back Tuesday with the continuation of Welcome to Charlottesville. Thanks for reading and please subscribe and share!

There were other reasons. Back in the day TV news bureaus were putting out 24 minutes a day while cable news puts out 24 hours a day; media companies were required to spend a certain amount on news; and antitrust laws were enforced to prevent media consolidation. Also the journalists had been through WWII which gave them a sense of what was at stake.

Which doesn’t mean video documentaries can’t be great. Three documentaries that freaked me out were Crumb, Grey Gardens, and The Act of Killing.

The growth in railroads and postal roads allowed for widely-distributed magazines, which improved opportunities, income, and training for writers.

Pew Research. Newspapers Fact Sheet.

85% of newspapers are owned by publishers who own other newspapers. Dirks, Van Essen, and April. History of Ownership Consolidation

https://transition.fcc.gov/osp/inc-report/INoC-1-Newspapers.pdf

Except for Knight Ridder chain which was then bought in 2006 by McClatchy.

By mentioning P.T. Barnum above I don’t mean publishers should embrace lying. Readers like lying in circuses, but for newspapers, readers want to trust what they read. Hype the trust by giving readers named, identifiable writers, editors, and reporters.

I’m guessing that the internet will become more monetized and that will reveal newsprint to be more competitive. But that’s a guess. I don’t really understand how the internet works.