Cville Begins!

Part 6 of of Welcome to Charlottesville, Blame Cannon's weekly visit to a town, a failed art project, and the future of America.

New Town

One of the great keys to human happiness is to limit your commute. A single journey can open our minds, sure, but regular, time-consuming travels over the same route wear us down in body and spirit.

This is the principle on which towns are formed.

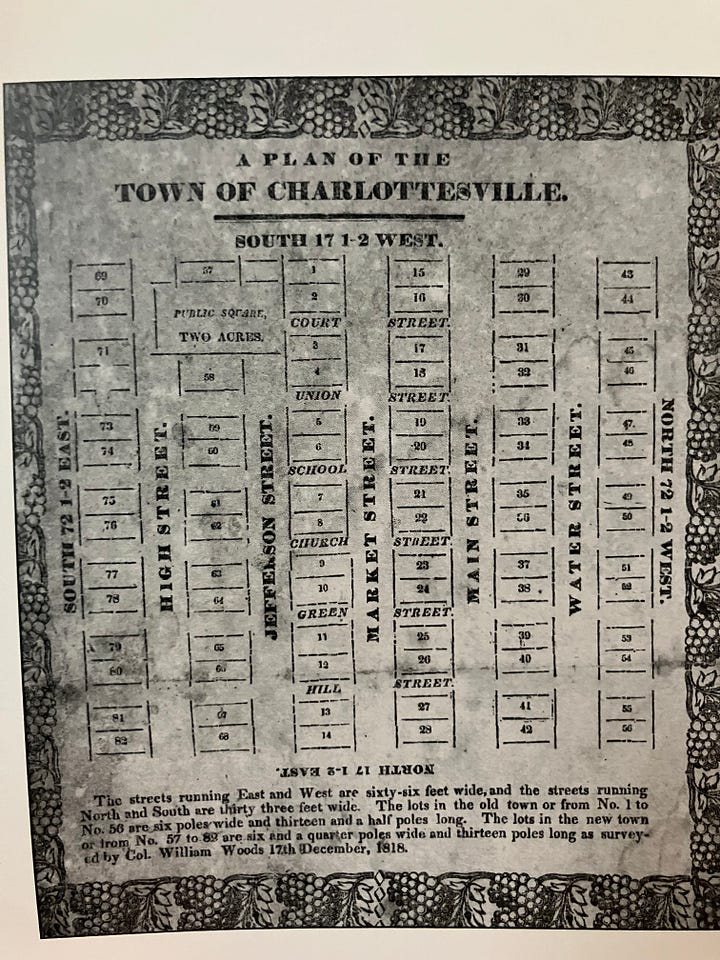

But we’ll get to that. The year was 1762. For a generation English-speaking planters and farmers in Albemarle County had made use of a courthouse in Scottsville for their legal deeds, lawsuits, and government needs. But that was a long way to go for those who lived in the northern part of the county, so planters petitioned the colonial assembly for a more-centralized county seat, and two days before Christmas Charlottesville was declared into being, a 50-acre grid named after Queen Charlotte of Mecklenberg-Strelitz who had only a year before married King George III, who himself only a year before that had been crowned king of England.

The lots were laid out by one of the leading planters, Dr Thomas Walker, setting aside a square for a future courthouse. With public money the courthouse with its jail, pillory, and a whipping post—the basics of frontier justice—went up quickly. The lots sold out rapidly too, but actual building was slower. A decade later there were less than twenty buildings in town including the Swan Tavern, our first watering hole.

If a weekly or monthly trip for a frontier planter is tedious, daily commutes for the rest of us are even more so. So Charlottesville’s original grid was tightly laid out, consisting north-to-south of what is now High, Jefferson, Market, Main, and Water Streets, running east to west from about 6th St NE to 2nd St NW. You could and can walk across this area in ten minutes. That was the point.

Old movies imagine people using horses the way people today use cars. Ride up to the saloon, swing a leg over to drop off the saddle, casually loop the reins over a horizontal pole, and mosey on in. Stay for hours, play cards, drink, shoot somebody, stay the night—whenever you leave that horse will still be waiting patiently. Real horses need a lot of care. On farms a horse can be taken to the barn pretty easily, but in towns and cities horses were usually kept stabled somewhere else, and brought out only for long-distance travel or special occasions. Daily life meant feet. So towns created cultures, laws, and architecture so people could get around on their feet.

Buildings were often built up against one another with residences above and various trades, shops, or businesses below. (This makes the daily commute time for many people two minutes.) This is the traditional pattern for building cities used since the Bronze Age: Buildings close or touching, residences above, work spaces below along narrow streets or alleys that open into public spaces.

Tobacco Road(s)

Humans mostly build towns along rivers. Before the English that’s how the Monacans did it. But Charlottesville is about a mile from the Rivanna on Three Notch’d Road, which ran between Richmond and the Shenandoah Valley roughly along the route of 250 today.

Roads mattered in Virginia in the 1760s because the primary export crop was tobacco—so primary that tobacco literally served as the colony’s money to pay wages or fees. Export crops, cash crops were too valuable to only be planted near rivers, so tobacco was grown wherever it could be, packed in giant barrels called hogsheads, and rolled to the closest waterway, to be floated to an official warehouses for weighing, sale, or taxation.

Chains

By 1762 chattel slavery had been the basis for growing tobacco for over a century, and tobacco was the basis of the planters’ legal and economic dominance. There was intellectual opposition based on Natural Rights and other Enlightenment philosophical ideas, and there had long been opposition based on the economic interests of the non-planter classes, but these weren’t very effective. Thomas Jefferson as a young lawyer tried a couple of ‘freedom suits’ which were basically laughed out of court. The colony of Georgia had been explicitly founded with an absolute prohibition on chattel slavery, yet the Trustees caved within a generation. During and immediately after the American Revolution, the northern states managed to end slavery, but none of the Southern states did so, and by the early 19th century even the intellectual opposition seemed to be replaced by new theories of pseudo-scientific racism.

The Slow Years

In 1801 the government had changed by act of the General Assembly to become five trustees to maintain streets, settle boundary disputes, authorize a market, cope with public nuisances, and appoint a town clerk.

Three local weekly newspaper followed in succession starting in 1820: The Central Gazette, The Virginia Advocate, and The Charlottesville Advocate. The final publication’s editor Harvey Wartman, ended up an important figure in the bi-racial, postwar Readjuster Party. (We’ll talk about the Readjusters when we get to Part 9 of Welcome to Charlottesville.)

Construction of the University of Virginia a mile from town began in 1819.

For its first century Charlottesville remained a small, sleepy place. By the 1850s the population was still probably less than 1000. Scottsville, with its access to a navigable river, was far more dynamic.

The Fast Years

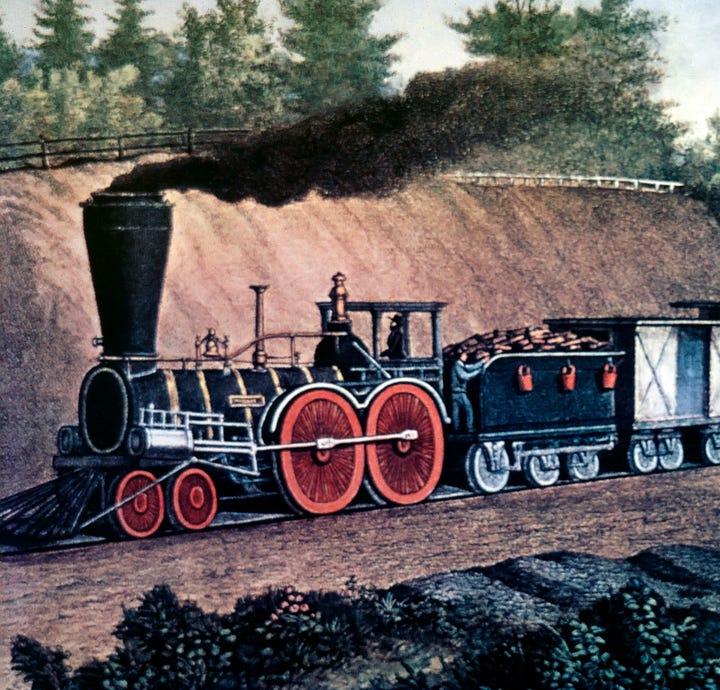

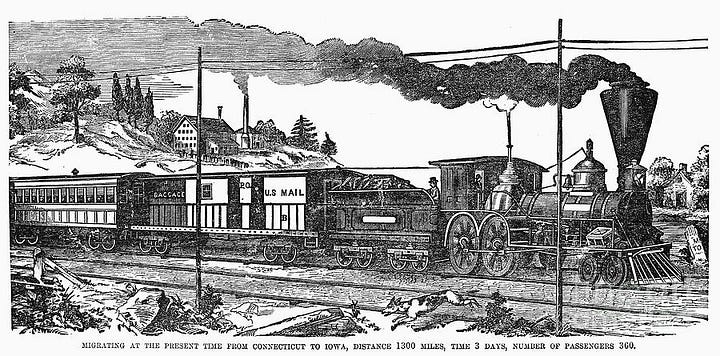

In 1850 came the Virginia Central Railroad. What automobiles did in the mid-20th century for suburbs, railroads did in the mid-19th century for cities. Major cities like London and New York grew into massive urban metropolises, but minor cities like Charlottesville experienced change that could feel even more dramatic. A trip to Richmond could now be made in five hours, instead of 3 days, and rail travel was cheaper than maintaining horses and carriages. (Second-class passengers could even help load the wood for the engines for reduced fare.)

Raw materials and finished goods could be shipped as well. Woolen Mills had been founded in 1830 but it was with the trains that it grew to make Charlottesville a center of manufacturing.

In 1860 Charlottesville got the telegraph and became a true railroad hub when the Orange and Alexandria Railroad ran a new line to Lynchburg. A passenger or merchant could ship in four different directions.

Civil War

Charlottesville was founded during the French and Indian War, a worldwide conflagration which began with Colonel George Washington leading a Virginia militia into the western wilderness, but that war never touched the central part of the colony directly. What it did do in many ways is cause the American Revolution. (A story for another time.) The Revolution brought the Hessians to town, and was the backdrop to Swan Tavern keeper Jack Jouett’s ride in 1781.

During the Civil War there were no major battles here. In 1865 the mayor, a man named George McIntire, either a businessman or a dentist, I can’t pin it down, surrendered the city to keep the town from being burned. And that brought the most important change.

March 3 is designated by the city as Liberation and Freedom Day, the date in 1865 when the Union Army moved in, and the Emancipation Proclamation took effect.

A year before, seeing the writing on the wall, a UVA professor of Greek and Hebrew named Basil L. Gildersleeve** published an essay on the dangers of “miscegenation”—claiming that to prevent it was to guarantee white supremacy. That is a good segue to what I think is the most important chapter in Charlottesville, Virginia, and maybe American history, the half-century after the Civil War. This was the time of the Readjuster Party, Redeemers, fusion parties, Grandfather Clauses, and the first fascist movements in the world.

Welcome to Charlottesville will take that time in three weeks.

Thanks for reading Blame Cannon! This has been Part 6 of Welcome to Charlottesville. Here are the sections in order: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5. Here’s the explanation. New chapters come out every Tuesday. Part 7 will be the story of my third time moving here, and Part 8 will near the end of the Police Stories project.

Please subscribe and share!

Comments are welcome but please no personal insults or profanity.

*Check out Scottsville Museum in Scottsville.

**https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/charlottesville-during-the-civil-war/