Coal Pt 2: How Coal Gave Us The Dinosaurs

How the shift from wood-burning to coal gave us geology, paleontology, archeology and the proof of deep time.

Winter at Blame Cannon invites you to enjoy a rotation of stories about global warming in prehistoric times, stories of memorable departures in my life, and stories of coal.

Wood to Coal: Food, Soap, and Women

In our first post on coal we saw that for some reason households in London in the early modern period shifted from open hearths in the center of their houses with no chimneys to fireplaces with chimneys at one end of a room with the advantages and disadvantages that brought.

And we saw how for some reason after that Londoners changed from burning wood to burning coal, which changed English cooking (The English medieval peas porridge nine days old of the nursery rhyme became Victorian-era pea soup.); cleaning (The Brits changed from wood ash to soap); and probably the perceptions and assumptions of Victorian womanhood. (Read the original for the deets.)

I grew up with the assumption that technological changes were usually positive, but for households not only were there serious disadvantages to fireplaces and chimneys, there were almost no advantages at all to burning coal (unless you really like pea soup) so why the switch?

The common sense assumption is that wood became too expensive, so people had no choice, but we saw (mostly through the work of historian Anton Howes) that this is unlikely. Firewood in England was an agricultural product, farmed over longer cycles than wheat or apples, but farmed nevertheless.1 Increases in demand for firewood should have led farmers to devote more land to growing firewood. So why did households switch? I suggested some possibilities, and since his earlier post Howes has returned with his thoughts on the subject which I’ll take up at a future time. But we really don’t know. But we do no the effects…

Households eventually switched to coal all over the British Isles, as industries like blacksmithing, glassblowing, and brewing had already done. Coal consumption surged decade by decade, so coal mining surged decade by decade, and the need to transport all this coal led to the digging of canals.

Below is a fellow named William Smith.

William Smith

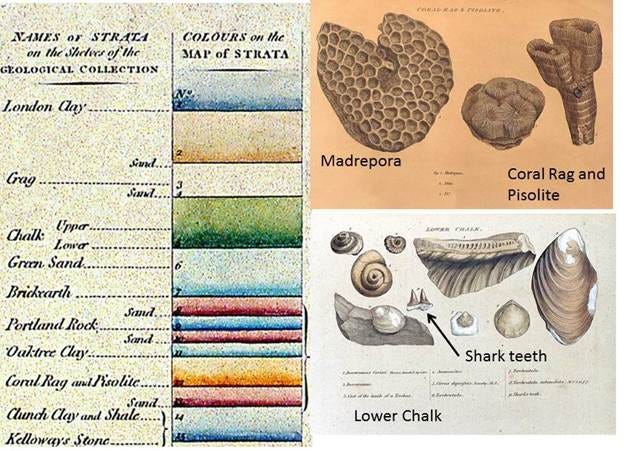

Smith was born in 1769 in Oxfordshire, England, the son of a blacksmith who died when he was eight, leaving him in the care of his uncle and namesake William Smith. He was self-educated, as many people seem to have been able to be at that time, and found a job as an assistant surveyor.2 He read widely, was industrious, and in 1799 Smith produced the first geological map in England, featuring the area around Bath where he did his surveying.

Then he started working for a company digging a canal to ship coal from Wales to Bath, so he traveled more, and in the process he inspected mines as well as seeing the exposed rock where the canals were being cut. Smith noticed that the layers of rock and fossils embedded in them followed regular patterns. Through his surveyor’s eye Smith could picture a stratified world undulating below the earth’s surface, layer below layer, each older than the one above.

From this experience (and reading other naturalists) Smith devised his ideas of stratigraphy.3 This is the study of the subsurface layers of the earth. A year after publishing a geological map of all England, Wales, and part of Scotland (which would have been enough for me) Smith in 1816 published a book, Strata Identified by Organized Fossils, which mapped how fossil groupings in Britain below ground corresponded with mineral layers region by region. Others had noticed such things before, but Smith systematized it, turning isolated and regional observations into organized data that anyone could study. He showed that particular fossils were associated with particular mineral strata—so each could predict the other—and that these relationships ebbed and flowed throughout the British Isles. He called it the Principle of Faunal Succession: a predictable arrangement of mineral layers and associated fossils stacked on top of one another. Which meant that in the British Isles some populations of creatures lived and died before others came into existence.

Unfortunately, Smith wasn’t as orderly with his finances as he was with his geological observations and books like Strata Identified by Organized Fossils never sold enough copies to make up the difference, so Smith found himself in debtor’s prison. Even when he was released he made it back home only to find a bailiff seizing his house and all its belongings.

So he went back to surveying, returning to where he began. But unlike many brilliant humans William Smith was recognized before he died. In the 1830s the Geological Society of London gave him a medal.

Deep Time

Smith got a medal and we all got deep time, not just as an idea but as data.

It’s important to understand that people in the past weren’t stupid. Long before Smith or large-scale commercial coal mines people understood what fossils were, and that a deeper fossil in a particular spot was likely older than a fossil above it, but people also knew that the geographic features of the world had changed. Volcanoes, earthquakes, floods, and erosion shifted and sometimes churned the earth. Fossils of sea shells could be found far inland. So a thinking person could not assume that a fossil in one location was older or younger than a fossil found many miles away.

Also long before Smith and large-scale commercial coal mines people had speculated about long spans of time. Mystics the world over contemplate eternity. Polybius and Giambattista Vico had imagined cycles of history, and others made all sorts of cross-cultural comparisons. And by the way almost no educated person in Europe took estimates of the biblical age of the earth as history or revealed truth.4 But speculation about time before written records was only speculation. So wise people allowed for the possibility of deep time but had no reason to accept it uncritically. There was no way to test it.

The unfortunately named Georges-Louis Leclerc Comte de Buffon—an important evolutionary thinker before Charles Darwin—used Leibniz’s hypothesis of the earth cooling down from an original molten state to calculate the age of the earth as at least 75,000 years. Not old by our standards but much older than Genesis.5 Other pre-Darwin evolutionists like J. B. Lamark, Benoit de Maillet, and Erasmus Darwin (grandfather of Charles) were certainly imagining an earth much older than a few thousand years.6 Non-evolutionists like Georges Cuvier was imagining an earth as old or older than the evolutionists.7 Historians of ideas may love these paradigm shifts but usually lots of ideas are floating around at once. What turned evolution from speculation to something approaching science wasn’t new ideas, but the new massive heap of data that William Smith provided.

Smith’s systematized description of huge areas, and his reconstructed fossil sequences allowed everyone to talk about the same things. Smith’s was one of the first generations to have the ability to see cross-sections of the earth in many locations at once because his was one of the first generations to dig so many holes and trenches all over the place.

It was irrefutably clear that the British Isles had passed through many ages or stages with different climate, vegetation, and animal life. Every stratum was one of those ages or stages. No one in the 19th century could be know how long each period of time was, but there were a lot of them and each must have taken at least thousands of years, so deep time was obvious. Now what each epoch should be called and where the borders should be set became a subject for debate. Today the sequence of geologic time is largely settled. What caused the shifts from each mineral layer with its associated fossils to a subsequent mineral layer with different associated fossils became a subject for more rancorous debate that goes on today. Some still see a gradual, orderly process like the old Lamarkians; others a gradual, competitive process like Darwin did; still others picture mass spasms of extinction and replacement like Cuvier.

But Smith created that data set that lets everyone debate and argue. He proved—so thoroughly that he has been forgotten along with any sense that such proof might be needed—that there was a long period dominated by trilobites and later a long period dominated by dinosaurs, and later still a time of mastodons and humans with stone tools hunting them. This meant the dinosaurs weren’t semi-mythical dragons off in some hidden land. They were creatures like us who once roamed the earth in plain sight and obscure now only because they lived very very long ago.

A New Dimension

Geology, paleontology, and archeology are inconceivable without the type of stratigraphy Smith pioneered and longer time scales it implied.8

Notions of whole “civilizations” being born, living, and dying left the historical framework of thinkers like Polybius and Vico, and became in the eyes of historians like Oswald Spengler and Arnold Toynbee

Notions of human “civilizations” each with a beginning, middle, and end left the provenance of the rise and fall of empires and entered the mainstream as a new kind of secular glory and end times. Without the stratigraphist perspective, not many Americans in the 20th century would likely have wondered if the U. S. of A. might “fall” as did the Roman Empire.

Every kid playing with dinosaurs, every theosophist contemplating Atlantis, every science fiction writer imagining time travel, and every doomscroller fearing an apocalypse is drawing on the layers of those pits of coal and the canals they funded.

First the trilobites, then the dinosaurs, then us.

Thanks for reading Blame Cannon! Next week we’ll use some of the tools of archeology to look back on the prehistoric climate change.

Please subscribe and share!

Comments are welcome but please no profanity or personal insults!

Family farming has traditionally been multigenerational. In ancient times it would take a decade for a planted olive tree to bear fruit (they’ve got that happening faster now according to the internet), which is why the olive branch was a symbol of peace. In wartime invading armies would cut down or burn the trees so there needed to be a lack of war for a longtime for olive trees, one of the central elements of Mediterranean culture, to pay off.

My brother Bret worked for a time as an assistant surveyor, so this post is dedicated to him.

He may have been inspired by an 1808 monograph by French mining instructor Alexandre Brongniart and French naturalist Georges Cuvier mapping combinations of mineral type and fossils from the Paris region, but Smith certainly expanded their work.

Even the people who pulled the books together to make the bible don’t seem to have seen it as history or revealed truth. At least not all of it.

Buffon also had an amusing spat with hometown boy Thomas Jefferson while the latter was minister to France. Buffon’s Histoire naturelle was the most popular book on what we call evolution at the time and read as widely as any popular scientist today. His evolutionary theory—elegant and wrong—was that as creatures migrated the climate in new territories gradually altered their physiology directly to create new species. As proof he claimed that European animals were bigger than those of North America. Jefferson, ever the intellectual, feared that Buffon’s notions of American inferiority might prejudice French support for the Americans in their war for independence against the British. Jefferson, Franklin, and Adams were there trying to get as much money and naval support as possible. So to prove Buffon wrong Jeffferson in 1786 wrote a militia captain in New Hampshire to send out a company to kill a moose and ship its carcass to France. Unfortunately, it arrived having decomposed too much to prove anything, so Jefferson wrote again and had another moose carcass shipped—both of these expeditions and shipments took place in the middle of the Revolutionary War—and this specimen arrived intact. It convinced Buffon who promised to change future editions of his work but died in 1788 before the slander could be removed. Luckily, the French government hadn’t based their foreign policy decisions on Histoire naturelle. Or at least they believed that American inferiority wouldn’t prevent them from harrassing Great Britain enough to serve as revenge for the Seven Years War.

Regarding evolution most textbooks repesent Catastrophism, Lamarkism, Natural Selection, and later the Modern Synthesis (combining Darwin’s Natural Selection with Gregor Mendel’s genetics) as being distinct phases, but in actuality, all coexisted sometimes in the same scientist well into the 20th century. Darwin’s Origin of the Species was championed for its account of evolution itself, not the mechanism of Natural Selection, which was not widely accepted even by Darwin’s defenders. Even arch-’Darwinist’ Thomas Huxley was a Lamarkian. Partly naturalists didn’t believe Darwin’s genetics would work as he described them (and they wouldn’t) and partly even the oldest estimated ages of the earth didn’t give enough time for Natural Selection to really work for all life.

Cuvier believed creatures would assume mature forms and remain in those forms until eventually a catastrophe hit and they would become extinct clearing the way for another set of flora and fauna. He claimed the biblical flood was perhaps a folk memory of the most recent of those catastrophic events. Dinosaurs dying by an asteroid or the mass extinction of the trilobites would have appealed to him.

Charles Lyell’s Principles of Geology is often cited as the basis for the older age of the earth and evolution. The book is entirely reliant on William Smith’s stratigraphy.