Goodbye Atlantis - Pt 1

Prehistoric climate changes and the legends of lost civilizations.

Welcome to Thera 1601 BC

Do not toss aside lightly the gifts of the gods, whatever glories they choose to give by their own free will.

—Homer, The Iliad III

One of the first things the archaeologist told us on the tour of Santorini in 1985 was that this is one of the possible sources for the legend of Atlantis.

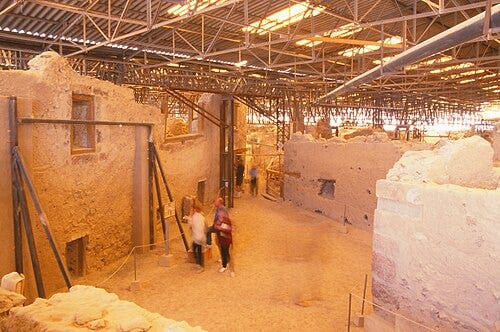

We were part of a college program in classics and archaeology in Greece that featured travel throughout the region including that trip to Santorini. The island was definitely a highlight. On its rugged surface it was one of those white-and-pale-blue village-filled beauties featured in tourist brochures, but in ancient times the Greeks called it Thera1 and the archaeologist—I can’t remember his name—led us down under a canopy roof through a maze of excavated walls, the skeleton of what had been a thriving city of paved streets, piped hot and cold running water, toilets and drainage systems, textile workshops, and gorgeous homes with exquisite frescoes—frescoes as colorful and beautiful as the works of nearby Minoan Crete.

Archaeologists call the excavated settlement Akrotiri after the nearest white-and-pale-blue modern village above ground, but this earlier Akrotiri was a wealthy, bustling port tied by art, trade, and culture to Minoan Crete and to nearby Mycenaean Greece, and beyond to the New Kingdom of Egypt, the city-states of Syria, Phoenicia, and the Hittite Empire—all the interconnected islands, states, empires, and cities that formed Late Bronze Age Civilization.

Late Bronze Age Civilization is one of the first undisputed capital-C “Civilization”—the first extended network of permanent agricultural settlements interconnected by trade and communications under the control of central governments, diplomats, armies, and navies. It’s the first political metastructure like the later Greco-Roman Empire, Imperial China, or the global system of our own time.2

Human foragers, farmers, and herders long before the Bronze Age traded and communicated over vast distances, but that trade worked like a bucket brigade, communications worked like a game of telephone. Individuals traded with individuals, travelers brought news with visits. Trust—always the true currency of human communities—relied on shared community rituals, guest-host relationships, kinship, marriage, and gift-giving. Kings and priests, when the existed, couldn’t—or didn’t—interdict or supersede these more decentralized ties.

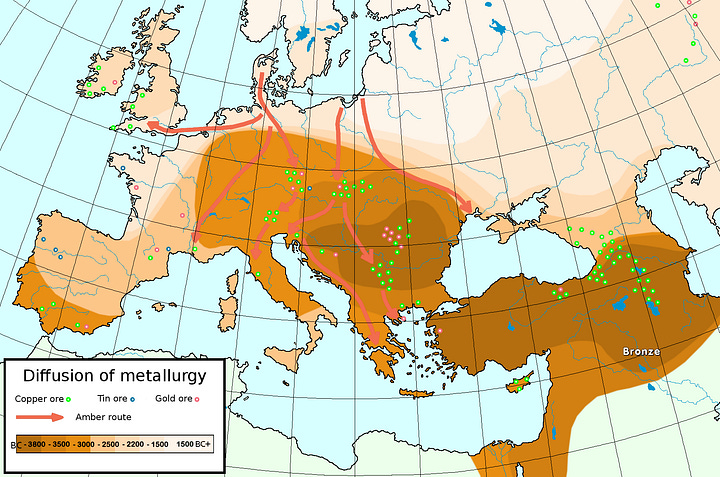

But in the Western Mediterranean between 3000 BC and 1600 BC some combination of writing, chariots, and bronze—and bronze’s constituent ingredients, copper and tin—induced a new layer of interdependence. Trust, began to rely on letters with seals, diplomats, trade, and pacts. Governments networked to keep the bronze moving as governments today network to keep the oil flowing.

Goodbye Thera 1600 BC

Thera at the time was a single conic island 9-10 miles in diameter. Alas, the cone turned out to be a volcano. About 1600 BC the volcano erupted, collapsing the center of the island completely, leaving only today’s crescent to the East and much smaller island to the West. The volcano roared and spewed for weeks. Minoan-era Akrotiri was utterly buried to be preserved for archaeologists as a Bronze-Age Pompey. The nearby Greek islands were destroyed too and remained uninhabited for centuries.

But the Theran eruption didn’t just affect the immediate area. Earthquakes, tsunamis, and falling ash and pumice covered towns on the coast of Crete and Rhodes a hundred miles away. The dust seeded brutal rainstorms that pounded Egypt seven hundred miles away. Yellow skies and summer frost were even reported in China, a quarter turn around the planet, making the Theran eruption probably the largest volcanic eruption in recorded history.

Those who suspect that civilizational collapse comes from natural disasters—such as those who fear the floods and storms of global warming will destroy our contemporary global system—must contend with the fact that the Thera volcano, as big as it was, had little widespread, long-term impact. Thera itself disappeared, but Crete and Egypt recovered, and the rest of Late Bronze Age Civilization went on to four more centuries of glory and prosperity.

When around 1200 BC civilizational collapse did hit the Late Bronze Age—A collapse literally called today the “Late Bronze Age Collapse”—there may have been droughts, plagues, and revolutions. Certainly there was a great deal of war. Egypt was attacked, the Hittite kingdom disintegrated, and the ruling classes of Mycenean and Minoan towns with their chariots, palaces, and writing were killed or expelled. But volcanoes and tsunamis played no part.

On mainland Greece, after the collapse, humans continued to live near the ruined palaces. There were fewer people and they were poorer—at least materially. This period is called the Greek Dark Age. The trade goods and fancy art from across the seas dried up, and the writing systems used in Crete and Greece disappeared entirely. When literacy returned centuries later, it was a new writing system borrowed from the Phoenicians.

Archaeologists mark a transition in the 700s BC from the Dark Age into the “archaic” period and that becomes around 500 BC “classical” Greece. Archaic and Classical Greece are the Greeces you learned about in school: philosophers, democracy, hoplite warfare, alphabetic writing, coins, plays, naked Olympic athletes, naked gods, sculptures of naked Olympic athletes and gods, and Sparta versus Athens.

It is from Athens in the Classical period and its second-most-famous native philosopher Plato that we learn about Atlantis.

I’ve heard Atlantis enthusiasts claim in YouTube clips that there’s an “Archaeological Establishment” that refuses to consider the possibility of Atlantis, but in my experience, nothing could be further from the truth. I can still hear the enthusiasm in that man’s voice back in 1985 at the mere possibility of Atlantis being associated with a physical place, and that joy has been matched by every historian, archaeologist, or classicist that I met in Greece or since. Who doesn’t love Atlantis? Every archaeologist would love to find ruins of the fabled land or an inscription on an Egyptian pillar to corroborate its existence. Every classicist would dream of finding a new, unknown literary work about Altantis.

All we have, however, is Plato.

Welcome to Athens 420 BC

Athens had been a second-tier place in Mycenaean times but became the major player in the classical period. The Athenians enacted a democratic constitution around 600 BC ascribed to a politician named Solon, and the new order gave the city a dynamism other cities lacked. A century later in 483 they got lucky too. The Athenians discovered a Mother Lode of silver in local mines. Having just fought a skirmish with the massive, looming Persian Empire, the formerly non-naval Athenians voted to use the money to build a fleet.

Three years later the Persians invaded the entire Greek peninsula and that new Athenian fleet defeated them at the Battle of Salamis. Soon after the Persians retreated and—spearheaded by the Athenian navy—Greek cities throughout the eastern Mediterranean flung off the Persian yoke and adopted democratic constitutions.

Unfortunately, within a generation Greek cities turned on one another in the Peloponnesian Wars, largely the Corinthians and Spartans and their allies against Athenians and their allies.

These wars ended badly for Athens, and Plato grew up watching it all go down. In his thirties he began writing dialogues, something like play scripts but meant to be read not staged.3

Twenty years into his writing career, around 375, BC Plato created his most influential dialogue, The Republic. The Republic is presented as a conversation taking place in Athens around 420 BC, before the Peloponnesian Wars ended badly. It features some friends and frenemies, including a semi-biographical version of Plato’s mentor, the first-most-famous philosopher from Athens, Socrates, discussing the ideal city or state. The “republic” of the title is Socrates’ contribution,4 which he describes in great detail. Note that Plato is setting the scene at a time when he was at most a few years old, so this wasn’t a conversation Plato witnessed or heard.

The dialogue seems to have been popular with many Athenians from the time Plato wrote it, and fifteen years later (around 360 BC) after a lot of travel and reflection, Plato cranked out a sequel. Maybe two sequels. Timaeus and Critias can be read as a single text, but most classicists break them up, so we will too.

Timaeus is set the day after the events in the Republic. Or something like those events. It doesn’t explicitly name that work. As the story opens we learn that Socrates was discussing the ideal state with friends the day before, but today most of those interlocutors are sick, so instead two guys named Hermocrates and Timaeus bring along someone named Critias. Neither Timaeus or Hermocrates are actually mentioned in the Republic, though they talk as if they were there. It seems like a bait-and-switch, but maybe they were listening in the background.

In any case Timaeus is a philosopher visiting from the Greek city of Locri in Calabria (A part of Italy). He seems to be fictional. Hermocrates is a historic figure, a general of the city-state of Syracuse in Sicily. (Also a part of Italy). Critias is also a historic figure. He’s a cousin of Plato who played a major role in Athenian politics, particularly during the period when that war ended badly. We’ll get to that in a future post.

Critias heard the others last night recounting this great conversation with Socrates about ideal governments, so today he’s tagged along to share a story he heard from his grandfather, also named Critias.

Hermocrates explains this and Critias jumps right in with a mention of Solon, the guy who wrote the Athenian constitution:

[Solon] was a relative and a dear friend of my great-grandfather, Dropides, as he himself says in many passages of his poems; and he told the story to Critias, my grandfather, who remembered and repeated it to us.5

Welcome to Sais 585 BC

The story goes that after writing his constitution Solon went on a long trip to give the Athenians time and space to implement it. Around 585 BC he visited an Egyptian town called Sais, and discovered that its people considered Sais a sort of sister-city to Athens due to their patron goddess resembling Athena, the patron goddess of the Athenians. The priests of Sais loved Athens so much they knew the city’s ancient history better than the Athenians did, including events from 9000 years before.

Many great and wonderful deeds are recorded of your state in our histories. But one of them exceeds all the rest in greatness and valor. For these histories tell of a mighty power which unprovoked made an expedition against the whole of Europe and Asia, and to which your city put an end…

Here it comes:

In this island of Atlantis there was a great and wonderful empire which had rule over the whole island and several others, and over parts of the continent, and, furthermore, the men of Atlantis had subjected the parts of Libya within the columns of Heracles as far as Egypt, and of Europe as far as Tyrrhenia. [Italy]

This vast power, gathered into one, endeavored to subdue at a blow our country and yours and the whole of the region… and then, Solon, your country shone forth, in the excellence of her virtue and strength…

Remember these are the Egyptian priests of Sais talking about Athens.

She defeated and triumphed over the invaders, and preserved from slavery those who were not yet subjugated, and generously liberated all the rest of us...

But afterwards there occurred violent earthquakes and floods; and in a single day and night of misfortune all your warlike men in a body sank into the earth, and the island of Atlantis in like manner disappeared in the depths of the sea.6

The rest of the dialogue then shifts to its title character, Timaeus, who talks about history (and prehistory) since creation, but says nothing about Atlantis.

Welcome to Atlantis 9500 BC

The second dialogue, Critias, picks up where Timaeus leaves off. Timaeus finishes his bit, and Critias takes up with the accounts from Sais. This is mostly about Athens 9000 years before, the Athens of which the priests of Sais (and Critias) allegedly know so much, but of which the other characters seem to know nothing.7

After describing the Athens of 9000 years before Critias moves on to Atlantis: “[T]hey were furnished with everything which they needed, both in the city and country.”

There’s descriptions of palaces and canals and such. There’s no mention of unusual technology, but there is one intriguing word: “[T]hey dug out of the earth… that which is now only a name and was then something more than a name, orichalcum, was dug out of the earth in many parts of the island, being more precious in those days than anything except gold.” Scholars know that orichalcum is some sort of copper-alloy or copper-like metal, based on the etymology, but no one knows it’s exact formulation today any more than Plato seems to.8

The dialogue ends this way:

Such was the vast power which the god settled in the lost island of Atlantis; and this he afterwards directed against our land for the following reasons, as tradition tells: For many generations, as long as the divine nature lasted in them, they were obedient to the laws, and well-affectioned towards the god, whose seed they were; for they possessed true and in every way great spirits, uniting gentleness with wisdom in the various chances of life, and in their intercourse with one another.

Sadly, it didn’t last:

[B]ut when the divine portion began to fade away, and became diluted too often and too much with the mortal admixture, and the human nature got the upper hand, they then, being unable to bear their fortune, behaved unseemly, and to him who had an eye to see grew visibly debased, for they were losing the fairest of their precious gifts; but to those who had no eye to see the true happiness, they appeared glorious and blessed at the very time when they were full of avarice and unrighteous power.

Zeus, the god of gods, who rules according to law, and is able to see into such things, perceiving that an honorable race was in a woeful plight, and wanting to inflict punishment on them, that they might be chastened and improve, collected all the gods into their most holy habitation, which, being placed in the center of the world, beholds all created things. And when he had called them together, he spake as follows…

That’s where it breaks off.

(Ancient literature is written on papyrus scrolls and quite often either the beginning or the end breaks off.)

Goodbye Atlantis

The rest of the dialogue is lost but we get the gist of what happened from that preview teaser in the Timaeus (quoted above), and from later writers who could read the full text. The Athenian warriors perished heroically defeating the Atlanteans, and then the gods in an act of divine retribution for their hubris sank the entire island of Atlantis beneath the sea.

Those two dialogues are all the information we have about Atlantis. All the legends, speculations, and hopes for Atlantis are based on them.9 Many of those legends, speculations, and hopes seem to ignore three critical facts:

First, the dialogues are about both Atlantis and Athens in a war with one another around 9420 BC, and while we don’t know where to look for Atlantis, we know exactly where to look for Athens. And it wasn’t there in 9420 BC. There was no permanent settlement in what become Athens, no metallurgy, and no farming until maybe 4000 BC at the earliest. Just foragers. Atlantis enthusiasts who imagine Plato as a credible reporter of primordial Atlantis never seem to explain why he so badly botches primordial Athens.

Second, large scale metal working leaves traces in the atmosphere that end up in arctic ice cores, so we know there was no extensive metallurgy anywhere in 9420 BC. Whatever Atlantis might have been, it wasn’t a technologically-advanced empire. Maybe there was some technologically advanced little island or town somewhere, but anything large enough to be called an empire, certainly anything as large as what Plato is describing needs lots of metal.

Third, and most importantly, even if Plato could have witnessed these conversations—and he never claims he did10 —or gotten transcripts—and where would those have come from?—the conversation described in Timaeus and Critias couldn’t have taken place because one of the characters, Hermocrates, wouldn’t have been in Athens. He would have been in Syracuse, Sicily, where he was the leading military commander.

You see, one of the major reasons the Peloponnesian Wars ended badly for Athens, was that during a lull in the fight with Sparta, the Athenians, urged by a young politician named Alcibiades, elected that selfsame Alcibiades general and gave him most of the Athenian fleet to sail off and conquer Syracuse. But instead their navy and army were obliterated. Alcibiades was one of Socrates’ most beloved proteges.

What brilliant general of Syracuse inflicted this catastrophic defeat?

You guessed it—the very man in the dialogs—Hermocrates!

The other major reason the Peloponnesian Wars ended badly for Athens, is that Sparta took advantage of the Sicilian catastrophe to go on the offensive, even building their own fleet, and eventually winning decisively at sea and land. The democratic government of Athens was overthrown by a junta, called the Dictatorship of the Forty Tyrants. The Forty subjected Athens to a reign of terror.

Who was the leader and architect of that brutal dictatorship—and by all accounts it’s most ruthless member? As it happens he was another of Socrates’ most beloved proteges and Plato’s cousin—the other historical figure in the dialogues.

You guessed it—Critias!

Did Plato draw on real legends or myths to create his dialogues? Maybe! We’ll take that up in a future post. Can oral histories preserve memories of disasters for thousands of years? Maybe! We’ll take that up too.

We’ll also take up Alcibiades, Critias, and the fall of Athens.

But whatever else we discover, Timaeus and Critias are indeed about a major war in which a once virtuous people create a great naval empire but gradually are corrupted by arrogance and impiety. These wicked people finally go too far and attack an innocent opponent who with the help of the gods fights back and defeats the overconfident invaders.

The actual war, of course, that Plato is describing is not between Atlantis and Athens, but between Athens and Syracuse. Athens is the villain even if that wouldn’t be comfortable for Plato to write in Athens itself in 375 BC. While the ending of Athens was not a volcano or tidal wave as was the ending of Plato’s Atlantis, it was a catastrophe real enough. Plato witnessed it as a young man, and the execution of his beloved Socrates was one of the aftershocks.

We’ll take that up next.

Next in our series: Goodbye Atlantis, Pt II: Why Socrates was guilty.

Here are other prehistoric global warming posts: Part I. Part II. Part III. Part IV. Part V.

Thanks for reading Blame Cannon!

Please subscribe and share!

Comments are welcome but please no profanity or personal insults!

Santorini was a medieval name, meaning Saint Irene. Irene of Roman was according to legend a widow of a Roman valet of Emperor Diocletian killed for his Christian faith. She tended the wounds of Saint Stephen, the guy in medieval pictures shot full of arrows. I have no idea why anyone named an island after her.

You could make the case that Egypt by itself or the earlier empires of the Fertile Crescent, like Hammurabi’s Babylon or Sumer before that met the definition, but there is an order of magnitude of interconnection and centralized control of states marked by the late Bronze Age. Of course “Civilization” carries a lot of baggage, but we’ll use it because I don’t know of anything better, and if we came up with a better word, I think it would rapidly acquire the same baggage anyway. The major powers of the Late Bronze Age tended to be hegemonic rather than explicit, like American, Russian, or Chinese influence in the world today as opposed to the more explicit rule by the Romans, China, or the 19th Century European empires.

There are examples of dialogues in ancient Sumerian literature, but Plato’s model came from his favorite writer, Sophron, who wrote comic prose dialogues. Sophron was a generation or two older than Plato and lived in Syracuse. Plato first applied this model to report on the trial of Socrates, taking up the pen to defend Socrates against accusations made against him by an Athenian named Polycrates in a work called Indictment of Socrates written around 493 BC. Both Sophron’s works and Polycrates’ are gone.

De Republica is the Classical Latin title for the Greek Politeia (Πολιτεία) which is hard to translate.

Read the whole thing here.

Read the whole thing here.

Orichalcum (ὀρείχαλκος) means something like “mountain copper” and refers to some shiny precious metal, perhaps a type of brass or white copper. It’s mentioned by Hesiod as a metal used in armor and in one of the Homeric Hymns as a metal used in earrings, so it wasn’t unique to Atlantis, and wasn’t any sort of fuel.

Plato himself may have drawn from another identified source, something apparently called Atlantis written by Hellanicus of Lesbos. This seems to have been a genealogy of the children of Atlas and Plato may have used it for his genealogy for the children of Poseidon who ruled Atlantis.

The dialogues were written sixty years after they took place about a visit to Egypt one hundred twenty-five years before that where the visitor is told about a war nine thousand years before that. That’s like if I was a protege of the linguist Noam Chomsky (I’m not) and I wrote an account of a conversation between Noam Chomsky and John Rawls that took place in 1966 (when I was two) in which Chomsky shares a story he heard from his grandfather originating from a tale John Adams brought back from France that reveals events in 7000 BC in America that Americans have never heard of.