The Real Difference Between Towns & Cities

And why Klingon has so many consonants...

Blame Cannon is about Charlottesville and other cities and towns.

But what is the difference between a town and a city?

Various government agencies, organizations, and authors use the words differently, but always with the vague sense that cities are bigger, fancier, or more important, or all three, but that’s more connotation than denotation. Why two words at all? The ancient Greeks used the same word, polis, for towns and cities. Why does English have two words?

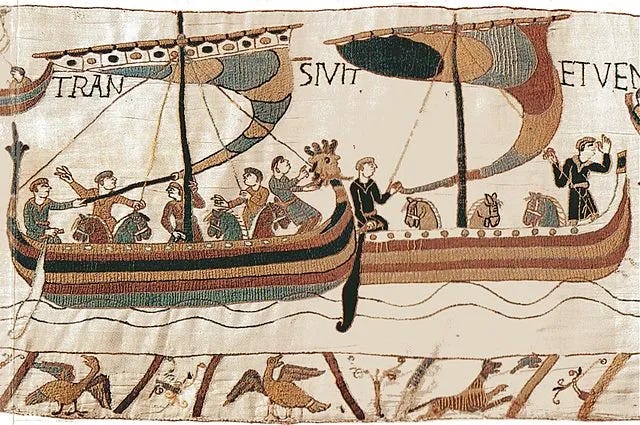

William the Conqueror

The answer goes back to 1066 AD when the Normans under the warlord William conquered England. The Normans spoke a dialect of French and the English spoke a Germanic language called Anglo-Saxon or Old-English. For the next four hundred years the ruling classes continued to speak French while the lowly peasants and tradesman spoke Germanic. Gradually both classes merged and the resulting middle is called Middle English.

Here’s the Lord’s Prayer in Old English, Middle English, and Modern English:

Fæder ure ðu ðe eart on heofenum (Old English)

Oure fadir that art in heuenes (Middle English)

Our father who is in heaven (Contemporary English)

The eue in Middle English was probably pronounced eve.

Dual Language

From Middle English until the Modern English we speak today the language has been a mix of French and Germanic. And the French-derived words still carry an aura of their ruling-class origins. Words like beautiful, artistic, eloquent, elegant, pleased, refined are of French origin. Germanic-derived words often still carry the connotations of the lower classes. Words like plain, strong, tough, straight-forward, happy, sturdy are originally Germanic words.

Sometimes there’s a French word and a Germanic word that denote the same thing, or almost the same thing, but their connotations are quite different. Consider the difference between French courage in a battle versus Germanic boldness in a fight. Or the French powerful maritime realm versus Germanic mighty seafaring kingdom. Retain versus keep. Possess versus own. Desire versus wish. Diligent labor is French. Hard work is Germanic. Animals are often described with Germanic words, cow, pig, and sheep, but the meat is often described by French words, beef, pork, and mutton.

Writers and speakers who know all this will often choose French or Germanic words to create a particular effect. Look at this culmination of a Winston Churchill speech:

Whatever the cost may be, we shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender..;

Only ‘cost’ and ‘surrender’ are of French origin; the rest are Germanic words.

Why Klingon Sounds Has So Many Consonants

So if you’re an English speaker making up a language for a science-fiction or fantasy world, and you want those characters to sound rough, strong, warlike, you’ll want that language to have some of the traits of Germanic languages, such as a lot of consonant clusters and guttural sounds.

Below is a Klingon phrase from the internet. Klingons—or at least these particular Klingons— were a fictional warlike people on Star Trek: The Next Generation.

Heghlu’meH QaQ jajvam! (Today is a good day to die!)

See all those consonants?! Lots of consonants means rough, tough, itching to stab you with a knife. Just like those Anglo-Saxon peasants.

Below is Dothraki phrase from the internet. The Dothraki are a fictional warlike people on Game of Thrones:

Hash yer dothrae chek asshekh? (Do you ride well today?)

See all those consonants?! Definitely uncivilized!

There’s nothing actually primitive or uncivilized about consonants. No anthropologist or linguist has ever posited a theory that primitive people have more consonants; it’s just what we as English speakers naturally associate with farms, herds, work, and war (all Germanic words by the way) because that’s the language of the common people hundreds of years ago. So if you ever need to create a science fiction or fantasy language to appeal to an English-speaking readership or viewership, now you know the secret!

Who says Blame Cannon isn’t practical?

So what are cities and towns?

So city is the French word and town is the Germanic work. Period. That’s the difference. It’s the same as the difference between a noble and a lord, royal and kingly, intelligent and smart. At Blame Cannon we’ll welcome all definitions of cities and towns, but we’ll be aware that they all just come down to the unconscious assumption that cities must somehow be more important or influential than towns, although towns might be more down-to-earth, because city is a French-derived word and town is a Germanic-derived word.

For my own writing, since both words exist I’ll try to make use of them. I’ll call places with lots of people living close to one another around some sort of public space towns, and inspired by the great urbanist Jane Jacobs I’ll use cities to describe towns with buildings of at least two stories with residences above and workspaces below close to similar buildings along narrow streets or alleys that open into larger spaces with markets and public buildings. The workspaces included specialized crafts or jobs. But you don’t have to think like me! I’d like to get past the current assumption that defining words and then arguing about them is the best way to share knowledge and opinions.

My only peeve is when people refuse to call small cities, cities. They want to reserve the word for the massive urban conglomerations like New York that arose with industrialization in the 19th century. I’ll call those places metropolitan cities, or industrial cities, or urban metropolises. They were a new thing that deserve their own term.

Once we have enough subscribers and readers for discussions, I’m fine with any use of words as long as we’re aware other people might use them differently.

Subscribe to Blame Cannon for regular Tuesday posts in the Welcome to Charlottesville Series, plus occasional bonus posts like this one!