Every third week I’ve been writing about memorable departures. Here are some others.

To Escape the System

1984-1985 was my junior year in college. I was a student in a program in Athens, Greece, called College Year in Athens. We lived in apartments near Kolonaki Square, studied classics, archeology and anthropology, and took field trips all over the Western Mediterranean organized by the program,1 During various breaks many of us took trips of our own in addition to or in place of the school’s program.

I loved CYA and liked everyone in it, but the people I was most drawn to were those who tried to do things in ways that were a little outside the system. Instead of nylon hiking gear and backpacks, we haggled for army-surplus rucksacks and jackets from the Plaka—then an open-air market. When traveling we would try to meet locals and take cheap transportation, not to blend in, but because other Americans didn’t. (We weren’t tourists, you see, we were travelers.) In all things we tried to be frugal, not out of greed, but because that would be more authentic.

Were we hipsters fifteen years too early or hippies fifteen years too late? Were we just idiots. I don’t think so. Since the 1970s breaking rules had become the mainstream culture. So normal teenage rule-breaking like smoking pot, vandalizing, speeding, or petty theft just felt like play-acting, like an antihero in a movie. Fun, yes, but not original or liberating. I wanted to feel free and I imagined feeling free might come from my decisions being rooted in my own desire, love, and wisdom rather than social rules or roles.2 And I suspect that’s what all my friends were after.

So during Spring Break when a CYA trip was scheduled for Egypt, several of us decided that it would be fun to travel to Egypt at the same time, but not as part of that official group. No tourist hotels. No tourist restaurants. Not prearranged itinerary. Not even the prearranged transportation that guidebooks written for travelers who don’t want official guidebooks said always to prearrange.3

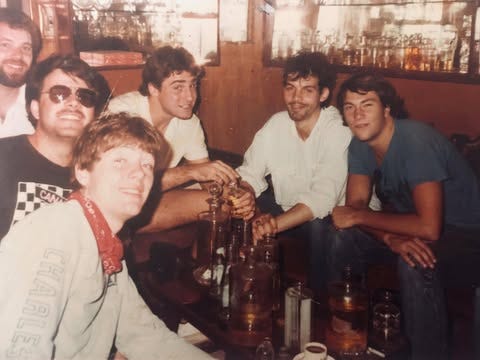

Chris had shaggy hair and sardonic slit eyes. He loved unusual people. He also loved the Grateful Dead and pot more than anyone should.4 Mike was from Florida, wanted to be a politician, had round saucer eyes like a cartoon animal when an anvil is falling. He often fell asleep on public floors after drinking. A different Mike from the New York area wanted to be a stock trader like his father and wore sunglasses indoors. Ray was soulful and sweet. (I’ve written about him here.) He was a year or two older and was the closest any of us were to maturity.

We flew to Cairo and immediately a man met us on the jostling, standing-room-only bus from the airport. (We didn’t take taxis even though they were cheap because that wouldn’t be as authentic.) The man took us to a hostel saying the other hostels would all be booked up and then talked us into giving him baksheesh. Baksheesh was the Egyptian word for gift or bribe.

For the next couple days we wandered around like the fools we were, getting mildly ripped off by restaurants, and vendors, pressed often for baksheesh by panhandlers and children, until we met up with an aggressive Egyptian man in a Members Only jacket5 and his nicer brother. Both spoke English well.

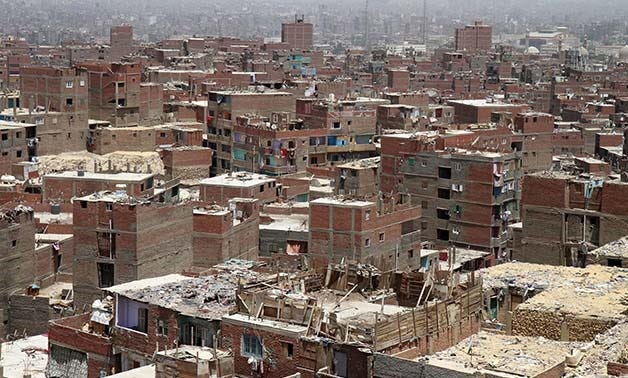

They took us to the shops of friends for souvenirs, and when Chris asked to buy pot from him, they took us that night to the slums of Giza to a four-room flat they shared with another brother, their wives, and their children.6 The flat was a corner of one floor of an unfinished cinderblock-and-brick building, one of countless tumbling into unlit dirt roads with strewn trash and barking dogs and the pyramids lit in the distance.

We five Americans and the Egyptian brothers all crammed into the tiny sitting room of the flat to listen to Chris’ Grateful Dead cassettes and theirs on a boombox. It turns out the Dead had played in Giza a few years before, and so they became a beloved American band. Then we drank hashish tea while the women and children peeked at us from the main room. The women laughed shyly at me, and one nice brother now in a jalabiya said they had never seen someone close up with blue eyes.

Then they took us up a flight of stairs to an unfinished floor. There were no walls, and the floor above was only partially completed so it was as sort of roof, sort of a cement deck. A half dozen Egyptian men and the four of us sat in a circle, all the Egyptians in jalabiyas except for Members Only. There was an lovely old man with a long beard and headscarf like an Arabian Gandalf. There were two hookas, I think, and maybe eight or nine small clay bowls lined up and packed with wet Egyptian tobacco topped with a few crumbs of hashish. The bowls were swapped out in the hookas and the hoses passed around.

Gandalf would smile and say “Welcome,” as he puffed enormous clouds out of both sides of his moth. The mix of hash and tobacco scorched by throat, but the women downstairs had laughed shyly at me and the old man kept saying Welcome, and the pyramids were lit on the horizon, so I couldn’t have been happier.

The Last Day In Cairo

The next day Members Only arranged horses for us to ride to the Steppe Pyramid. I found I loved riding (I’d never done it) and at the Steppe Pyramid a group of school children surrounded me and the teacher again said they had never seen blue eyes.

We decided that after visiting the Great Pyramid and Sphinx we would leave Cairo for Luxor, a smaller city upriver. Really they all decided, and I happily went along, which is what I did. Luxor was Thebes in ancient times, the capital of the kingdom of the Pharoahs.

Remember though, that we were travelers, not tourists. So instead of buying the first class tickets from an official travel agent for $15, like the guidebooks all recommended, we decided we’d just get the tickets at the train station. The Egyptians do it; how hard could it be?

Also why waste a day on a train and sleep at some hostel at night? Instead we’ll take a night train, sleep on it, and arrive refreshed and ready for a full day in Luxor.

We’ll get to the train station a couple hours early for the 11 o’clock train just to be safe.

At this point, however, Ray had had enough and decided to stay in Cairo. He was put off by all of us, but especially Members Only. Aggressive people were drawn to Ray like cats are to cat-haters. Ray’s pained brown eyes enticed them to sit next to him and tell him more. Aggressive were also drawn to Chris too, since he had an air of command. Or they would yammer at Trader Mike or Politician Mike. Aggressive people never talked to me—and still don’t. I used to compliment myself that this was because I have some innate goodness that drives them off, but I think it’s more that they immediately think I’m an idiot.

Ray’s departure does mean more space in the taxi. Unfortunately, Cairo is huge and crazy, so we were slow to get organized, and then we had trouble getting a cab cause we were too authentic to be in the tourist areas where the cabs were, and the cab got stuck in Cairo’s perpetual traffic jams—maybe just to run up the meter—so by the time we got to the station it was a little after 10 and we have less than an hour.

The station is a sprawling jumble of massive tiled rooms connected by bent and squalid tunnels. Everywhere wander crippled beggars, shouting peddlers, belt-thumbing cops, and vacant-eyed third world families with a look of weariness that isn’t the nihilism of the Russians twenty years ago or Americans today, but a human population after a dozen empires have crashed and a half-dozen entire civilizations. They certainly aren’t breaking rules to try to be authentic. The system cannot be beaten; only endured.

We pile our bags by a pillar of a cavernous chamber or ticket windows. I’m to watch the bags while Chris goes off through the tunnels to find the right platform. Mike and Mike stake places in different snaking lines. Ticket windows have signs that are covered over with other signs and pieces of cardboard and taped out and painted out areas and other pieces of cardboard and finally the actual relevant information seems to be written in pencil on small pieces of paper. All in Arabic.

Finally, with only fifteen minutes before the train departs one of the Mikes make it to the front of a line. The other Mike joins him and after a worrisome discussion, I see them trying to baksheesh the guy. The guy even disappears from the window a couple times only to return.

That distracts me long enough that when I look back a little girl in a filthy dress and long tangled hair is lying asleep on my Greek Army surplus knapsack. Hello! I say loudly but she doesn’t move. I’m scared to touch her for fear someone might rush over to claim I was trying to accost or kidnap her. I’m looking around for a parent but no one seems to be nearby.

Finally, with less than five minutes to go, Mike and Mike and Chris coming rushing back.

“We could only get third class.”

They take off toward the tunnel and I am trying to slip the knapsack out from underneath the kid without her head conking on the floor, but I can’t get her to wake up. Mike, Mike, and Chris are gone. Finally, I slide the backpack gently away, dropping her head into lower and lower creases, until the backpack comes free and the kid does conk a little, and I feel it in my gut, but still she doesn’t wake up. I can still hear that little conk today.

Now I’m running after the others through the up and down tunnels toward the platform past tables and beggars and entire families camped in the open space.

Even the roughing-it-type guidebooks said don’t travel third class. Maybe we can sneak into first class or upgrade on the train. Anyway how bad could third class be?

We emerge onto a platform with a rumbling train. Almost all of the doors are closed, but there is one open door with a conductor leaning out. He beckons to us to hurry. “Come! Come!” he shouts in English.

We run.

The Train

We reach the train and climb up the steep stairs into an enclosed space between between two cars. It’s much larger than on Amtrak trains. Metal plates screech over the couplings and between the cars as the train starts moving. There are wall sections extending from each car with the door commecting to one another with a heavy accordion of cracked black rubber.

The conductor greets us in English, “Welcome, welcome. Please to see tickets.”

He glances toward the door on our left—presumably the door to the first class area since as Americans he must expect us to travel first class—and waits as Politician Mike digs out small cardboard squares.

When the conductor sees our tickets his face shows confusion and maybe a little fear. He glances toward the door on our right, the door to the other car.

It originally must have looked like the door on the left but the door on the right is dented in several places and a metal crossbar has been welded to it. The crossbar is wrapped in chains and padlocked. The door to the third-class compartment is chained and padlocked. Like a cattle car.

At the sight of the chains, all of us share a rising panic. Especially as we feel the train accelerating. We start the epic session of baksheesh. Wait, sir, we paid for first class tickets and the they must have given us these by mistake. Of course we won’t dwell on the mistake so just let us upgrade here by paying you money now. Just let us upgrade with you and we’ll include a processing fee in Egyptian currency. Let’s upgrade with you and we’ll included a processing fee in American dollars. Please. Finally, he looks at the chained door and looks at us and accepts twenty American dollars to allow us to stay here on the metal plate between the cars.

We’re ecstatic.

We build a pile of backpacks and army jackets in the center of the shifting metal. We lounge on top and share oranges and bread and bottled water as the train rumbles and creaks beneath. It’s too noisy for conversation or to hear a Grateful Dead cassette in Chris’ boombox, so I play harmonica along with the train noise and it’s the rare time, other than campfires on beaches, when harmonicas don’t annoy anyone.

We did it! We beat the system. We’ll doze and smoke cigarettes and be in Luxor by tomorrow.

Until two hours later the door to the first class opens and a different, bigger, meaner conductor steps out and sees us. He goes ballistic.

He demands tickets, yelling in Arabic as he pulls us to our feet, and when he sees we’re third class he immediately begins unlocking the padlock to the third class section. No arguments. We offer Egyptian currency, US dollars, we offer a pair of blue jeans, but he will not be bribed.

He unwraps the chain, screeches open the door to reveal a pitch black maw. We and our belongings are shoved in. The door clangs shut behind us.

First is the smell. A thick choking fog of sweat and cigarette smoke.

Then our eyes adjust. The car is, or was, once similar to an American commuter train. Pairs of seats face one another perpendicular to a center aisle. A luggage rack on each side overhead runs the length of car. There are a few still-functioning overhead lights glowing grim yellow and reflecting off the windows. The windows themselves are so caked in grime that they look like the dryer filters. In the back an white eerie glow reflects off a pool of water or sewage in the doorway of what is or was a bathroom.

All the seats and an area of floor and even parts of the luggage rack are packed with Egyptian men—all men—something like 150 Egyptian men—and they’re all staring at us. A few whisper to one another and there’s Dickensian coughing here and there, but once the door behind us is chained there’s no other sound but the train’s own rumble.

We’re four Americans in the 1980s with hundreds of U.S. dollars hidden in pouches and packets—hard currency—locked in with a hundred men for whom that amount of money could sustain a family for a year. No baksheesh here. None of us are dumb enough to flash money around. There’s no more beating the system. All we can do is clutch our belongings and see what happens.

We stand in this tiny area near the door, unable to move, holding our belongings, trying not to look scared. We wait. And wait. About fifteen minutes go by.

The Egyptians lose interest. They go back to quiet, whispered conversations around shared cigarettes. Almost everyone seems to be sharing a cigarette.

After a half an hour an Egyptian man stands and beckons for Chris. Chris shrugs and follows him. They sit him down in a seat and surround him with five Egyptians and offer him a cigarette that he smokes with them, passing it back and forth. Chris normally doesn’t smoke. Usually he tucks gift cigarettes behind his ear. But he sure is smoking tonight.

Politician Mike crawls up in the luggage rack, dangling his legs like a gargoyle with his face pressed almost to his knees. Somehow he immediately falls asleep. It’s the most incredible act of sleep I’ve ever seen. The Egyptians below him don’t seem to object.

It’s just me and Trader Mike.

After another hour there are a couple stops. The chains are unlocked, the door creaks open like a tomb pried with crowbars. Men leave and men enter, snaking past us, and then the clang as the door is resealed. There are sometimes open seats but Trader Mike and I do not move toward them without an invitation.

An hour goes by until Trader Mike gets invited to sit. Like Chris he’s surrounded and offered a cigarette which he shares passing it back and forth like a joint.

More hours go by. Too many. More stops. My legs are like cement. When the train is moving I concentrate to keep my knees from buckling. It’s predawn now and there’s some light in the train filtered sepia by the filth on the windows. I see a waving hand. The train is turning Southwest so the light is in my eyes and the Egyptians are silhouetted with gold.

Someone closer to me tugs my sleeve and points back down the car at the waving hand. I stumble toward it and its shadow-hidden face. The shadow gestures toward the seat across from him and its only occupant moves to one side to give me space and nods. I sit in the seat and nod. The man across from me lights a cigarette and offers it. I crave the stimulation, the harsh Egyptian tobacco, something other than the numbing ache of standing. I take it an inhale and we pass the cigarette back and forth a few times in the dark, each taking a puff. I try to offer it to the man sitting next to me but he shakes his head no. Mostly I try to gaze out the window behind him to avoid the horizon sun in my eyes, but the window is so filthy it’s opaque.

Now the sun is rising, and the man is handing me the cigarette about the fourth time, the train is slowly creaking to the southeast so the diagonal golden light sweeps upward. It rises slowly over and stretches across his face, and his face—half his face, that is—is missing.

He has some sort of disease eating into his cheeks and one of his eyes and nose so that chunks of his flesh are gone. And I glance at the others as if they might acknowledge the horror, but they all only stare that third world stare. They’ve seen rotting faces before. That could be their faces rotting. It might be next year.

I look back at the diseased man and he’s still holding out the cigarette. I could refuse it now. I owe nothing to him. But that might hurt his feelings, hurt his reputation. So I take the offered cigarette, inhale deeply, and pass it back to him as the sun comes up.

And for that morning I felt free.

Thanks for reading Blame Cannon! For the next couple of months I’ll circle between a series on global warming in prehistory, a story about coal, and a series of true stories about departures and goodbyes.

Please subscribe and share!

Comments are welcome but please no personal insults or profanity.

This was the original profile of “Generation X” presented in the novel of that name by Douglass Coupland. Coupland’s generation X consisted of people born in the 60s who had no personal connection or memories of the counter-culture of the 1960s which became the mainstream culture of the 1970s and was fully commercialized by the 1980s.

Fortunately, back in the 1980s there were enough young people who wanted to travel in free, non-sanctioned ways, that there were guidebooks on how to do this: Let’s Go, Lonely Planet, and Rough Guide offered sites, lodging, transportation, and meal possibilities in compact portable form. But even the guidebooks said not to do what we did in Egypt.

What did the Deadhead say when he stopped smoking pot?

”Turn this sh*t off!”

Members Only jackets were trendy puffs of 1980ness. I only ever owned one, a white one with sleek hide-away zippers and the perky snap-up epaulets. I purchased it before going to Greece, and saved it to wear on my Sept 29th birthday. Finally, the day came. I wore it to celebrate and lost it that night at a disco in Kolonaki Square.

In anthropological terms I never could figure out if the three families who shared the apartment were headed by actual brothers (patrilocal), brothers by marriage (matrilocal), or were distant cousins or just friends who adopted fictive kinship in order to share such a small space.