My aunt recently passed away. She asked me to share my opinions about what we can do in response to the cascading abuses of the Trump presidency and our government in general. I don’t pretend my opinions matter, but my aunt asked, so I’m doing my best.

A Glimmer of Hope

These are plenty of specific policy choices that could benefit a country—universal health care, changes in zoning laws and housing, and shifts to land taxes—but the big three basics that need to happen for effective government in the United States, or anywhere are:

Any government must tax the rich (We discussed this in Part 1)

Rein in military spending (which we’ll get to in Part 4)

Break up monopolies (which is today’s subject.)

The first two will not happen under Trump’s presidency, so any hope that Trump will set us in the right direction—intentionally or not—is pure fantasy. Moreover when (and if) the Democrats return to power, their leaders have made it clear they will also not tax the rich or cut military spending in any substantial way. Plus any actual reform efforts that appear will have to contend with revanchist elements that Trump’s habitual lawlessness will leave embedded in the government. These elements will make Trump’s first-term struggles with the federal bureaucracy (“The Deep State”) seem tame in comparison.1

So we have decades of misery and chaos ahead.

The one area for hope up until a couple days ago was breaking up monopolies.

One of the worst parts of the Reagan-Clinton consensus has been the allowance—really the encouragement—of cartels and monopolies by administration after administration. Although the Biden crew was mostly pro-corporate and contributed nothing toward antitrust some members of a presidential administration for the first time since the Carter administration really took on corporate power, and it was making a difference. They challenged non-compete clauses, attacked pharmacy benefit managers, and sued quite a few big companies.

Surprisingly, the Trump administration didn’t toss all that away, but was going forward with antitrust court cases started under Biden, including important cases against Amazon, Facebook, and Google.

Then a couple days ago House Republican Judiciary Chair Jim Jordan announced that he was planning to use the budgetary process to cut out a key pillar of antitrust law, putting existing antitrust cases in jeopardy. Jordan wants to gut Section 5 of the FTC law.

This area of law has been used for more than a hundred years to address illegal commissions, firms spying on rivals, sabotage, messing around with patents or regulations, and addressing mergers or exclusive arrangements that didn’t quite meet Sherman or Clayton Act standards.

The quote is from Matt Stoller’s newsletter, Big. Big is a regular report on the current state of monopoly and its opponents, current antitrust cases, investigations into various industries—from agriculture to housing to eggs to lumber to music—and reports on what the government is doing about all this (usually not much!). Just the absolute best thing of its kind on the internet by a skilled thinker, researcher, and writer, and must reading.

Here’s a few standalone pieces:

Here’s an old piece on guitars to give a sense of how long he’s been doing this

I don’t need to rehash Stoller’s piece on the Republican rule changes. Read the original. And then subscribe and read weekly!

What I want to do today is step back for the bigger picture on America and corporations.

In Antitrust we Trust

The hard-won wisdom of the first Gilded Age, reinforced by the Great Depression, and the spectacle of communist and fascist governments rising in Europe, was that cartels, monopolies, trusts, and oligopolies needed to be broken up by the government for the good of everyone.

So they wrote laws and created agencies to do so:

The Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 made it expressly illegal for individuals, businesses, or groups of businesses to restrain, corner, or monopolize markets.

The Clayton Antitrust Act of 1914 further made it illegal for individuals or businesses to offer different prices to different buyers, negotiate exclusive agreements, merge different companies that would lessen market competition, or for individuals to serve in leadership positions for competing companies.

The Federal Trade Commission Act of 1914 created the Federal Trade Commission largely to enforce the Clayton Antitrust Act. Before the FTC enforcement depended on the zeal of particular administrations.

The Robinson-Patman Act of 1936 expanded aspects of the Clayton Act to explicitly bar special pricing or delivery for chains over small businesses.

What all this means that the special distribution deals that big box stores have are explicitly illegal, most big box “store brands” are mostly illegal, and the big box stores themselves are arguably illegal.

So why are there so many big box stores and store brands? Because many well-meaning people during the Reagan and Clinton administrations—both Democrats and Republicans—believed that consolidating industries would lead to greater efficiency and therefore lower prices for consumers. Economists believed this, politicians believed this, pundits believed it. It turns out they were wrong.2

That has been very bad. But maybe just as bad—possibly worse—was that they didn’t have the votes to change antitrust laws, so the Reagan, Clinton, Bush I, Obama, and Bush II simply stopped enforcement.3 In blind trust of abstract “markets” they ignored a whole body of laws, laws written to prevent monopolies and cartels began to be ignored, laws the executive branch was obligated to enforce. This not only allowed America to become the oligopoly it is today, but created the precedent of presidents picking and choosing their constituional responsibilities like suburbanites at a buffet, and that precedent is playing out fully now with Trump.4 Think how crazy it is that instead of repealing a law, presidential administrations starting with Reagan, just said, We’re not going to enforce what we don’t want to enforce.

Will Jim Jordan succeed at doing what even Trump didn’t seem intent on doing? Will the Democrats in the Senate oppose him? It might be amusing to watch Democrats—who for decades were content to see antitrust laws ignored—suddenly declare these laws the soul of our republic.5 But more probably they’ll simply cave so Chuck Schumer can get back to his book tour.

Markets and Corporations

All markets are government creations. In the absence of government trade moves through social ties to achieve resilience, not competition to achieve efficiency. If we’re peasant farmers trading butter for eggs what I want is eggs on a regular basis, a relationship of mutual respect that accords us both status in our community, an alliance in times of emergency, and a family for my children or their children potentially to marry into. I don’t need six eggs instead of five. Until a government provides safe spaces for transport, trade, and markets; a currency to facilitate exchange between strangers; and laws and courts to enforce contracts; getting the best price is the least of anyone’s concerns. Without government we want trustworthy human connections more than good deals. Greedy people who bicker about the price of things are mocked in most folk cultures. Such behavior is understandable for widows or childless old people since that’s what they’re reduced to, but among adults in their prime outside the reach of government trustworthy family and social connections and a reputation for being fair, capable, and generous is the rational ideal.6

Regular markets as we understand them don’t appear on the planet till around the 7th century BC in the Mediterranean area.7 Such markets were physical spaces—literal marketplaces—where merchants used coins of precious metal stamped by a government to guarantee weight and purity, to facilitate exchange between strangers. The agora of so many Greek cities, the forum of Rome—these were government-policed spaces (supported by legal systems), that taxed back some of the coins to encourage their use and to raise revenue.8

Corporations, as we know them, come from Roman law.9 The word derives from corpus, body, and means body that is created. Corporate laws allowed religious groups, trade associations, and political groups to act as a single body for owning property, negotiations, and court appearances. So one person could represent everyone in a lawsuit or contract, so not every member of the group would have to be present. During the Middle Ages corporate concepts were used to establish abbeys, guilds, mercantile groups, and especially cities, and in the process was implied a degree of limited liability. If a monastery was responsible for starting a fire that destroyed a ship, individual monks who were not directly involved would not be personally liable. Even if the monastery went bankrupt paying damages and had to sell off all its assets, individual members were free of further obligation. If the Abbot lit the fire, he would still be liable—limited liability doesn’t mean no liability—but monks who were not present would not owe anything. That’s essentially why cities and towns incorporate. Without limited liability, if Charlottesville was sued for an icy sidewalk, all of us in the city would be liable.

In lore of the left the problem began with the 1886 Supreme Court case, Santa Clara County v. Southern Pacific Railroad, during which the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment was extended to a corporations, giving corporations legal “personhood” and leading eventually to Citizens United. This isn’t really what happened in the Santa Clara case, not what the actual decision said, but it Citizens United was a terrible judgment, and the way courts have rooted their history in early case has contributed.

But whether corporations are people or not doesn’t matter as much as whether they are cornering markets and controling supply chains, and that is a function of their size, practices, and market share more than their abstract personhood in the eyes of judicial opinions. If the biggest corporations were local factories, if Uber was just an app, if Amazon was just a website, their limited size would limit their political contributions far more effectively than any law would need to. Politicians in the first Gilded Age went through this, and they realized that what matters most isn’t the definition of corporations but protecting supply chains and markets from predation.

Jefferson versus Hamilton

At the time of the American Revolution and early Republic massive corporations independent of governments didn’t exist, so they just aren’t talked about in the founding documents like the Federalist Papers. The few major financial and business corporations like the Dutch East India Company and the British East India Company, were chartered by monarchs, and acted as privatized departments of government. The “terrorists” carrying out the Boston Tea Party understood their actions as a blow against the British government.

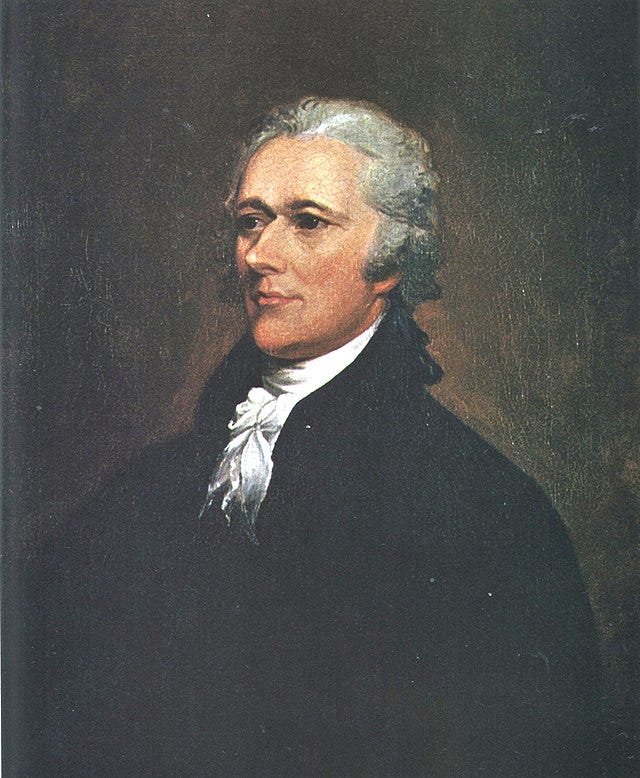

Nevertheless, as soon as the British monarchy was overthrown, businesses and finance became the source of one of the second major rift in our political history.10 When the Constitution was ratified and George Washington became the first President, the political world quickly divided between the first Secretary of the Treasury, Alexander Hamilton, and the first Secretary of State, Thomas Jefferson. Each feared the other’s approach to government.

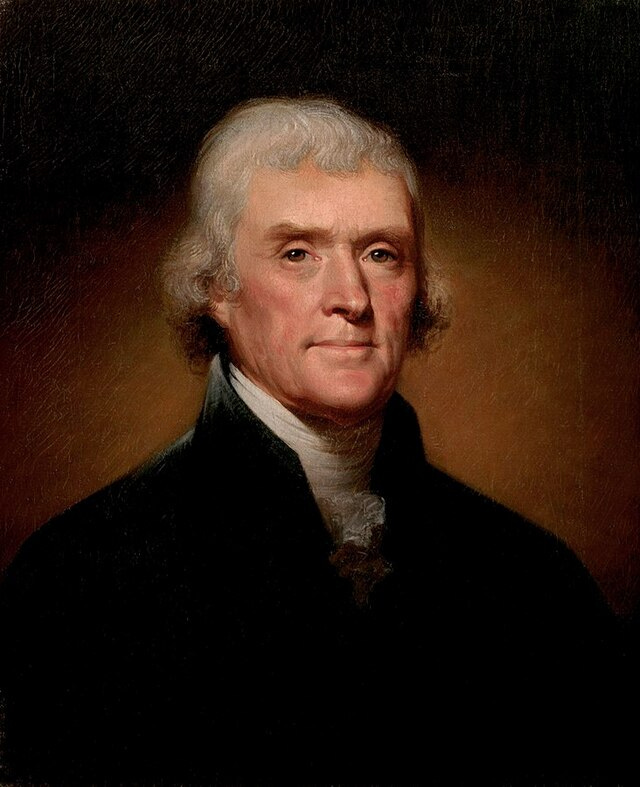

Jefferson believed the United States was the last, best chance to prove that human beings could govern themselves over an extended territory based on humanist principles and without a hereditary monarch, state religion, or corrupt ties knotting the government to the ruling classes. He was also cared about ending slavery, and seeing the United States succeed as conventional nations were judged—though both of these goals were less important than the first.

Hamilton most wanted the United States to be a powerful, successful nation as conventional nations were judged. He was also interested in ending slavery, and seeing if a human beings could govern themselves over an extended territory without monarchy or state church. But since he wanted the strong country most and sincerely doubted self-government would work anyway, he believed it was essential to tie the interests of the ruling classes to the government through what his opponents called “corruption”—a word he himself playfully used. Corruption was a positive force for social and political stability.

Jefferson was horrified. He foresaw Hamilton’s approach leading to business interests controlling the government and masses living in absolute squalor of the type he had seen in pre-Revolutionary France.

Hamilton countered that Jefferson’s approach would lead a weak central government unable to manage a crisis, so that regional and state powers would go their own way and come into conflict with one another.

Who was right? Well, in the struggles that followed Jefferson defeated Hamilton and the Jeffersonian system was imposed leading to… exactly the problems Hamilton warned about! Then during the Civil War the Lincoln administration struggling with the scale of the war imposed a version of the Hamiltonian system which led to… exactly the problems Jefferson warned about!

It turns out that government is hard.11

Gradually the power that the Hamiltonian system vested in the central government was used by reformers to put corporations in check. (Until Reagan and Clinton cut them lose again.) But neither Jefferson nor Hamilton—nor Madison, Adams, Montesquieu, or Locke—came up with structural, constitutional mechanisms to break up corporate consolidation. Great minds spent the better part of two centuries trying to figure out how to escape the problems of state churches, hereditary kings, and titled nobility, but we don’t have a similar body of thought on corporations. At best we have a few laws and agencies that can be used if a particular presidential administration chooses to use them.

The Second Gilded Age

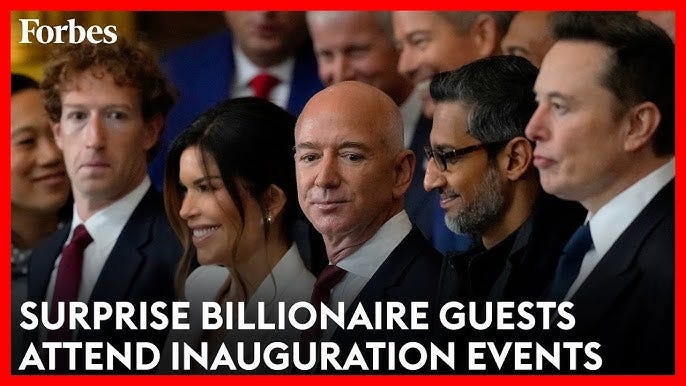

No matter what happens with tariffs, wars, taxes, the stock market, or anything else, life in this country during our Second Gilded Age will not get better until American governments learn from the First Gilded Age and break up monopolies. We are misgoverned mostly because we fail to tax our rich people, but our standards of living and quality of life are falling mostly because we have allowed corporate consolidation. Yes, foreign competition, budget deficits, the dollar, and wars do contribute to inflation, but solving all those won’t do much if corporations can just buy up their competitors and corner markets. Even if tariffs did whatever Trump thinks they’ll do (and we’ll take that up down the road), that won’t mean anything if corporations are able to buy up their competitors and corner markets. Right now most of those tech giants attending Trump’s inaugural aren’t competing against anyone. They know they’re operating in blatant violation of antitrust law—even if their stockholders haven’t realized it—and that’s why they’re sucking up to Trump.

Nothing is going to get better until monopolies are broken.

Next: Of Arms and their Budgets.

Thanks for reading Blame Cannon!

Please subscribe and share!

Comments are welcome but please no profanity or personal insults!

Needless to say, all the principled conservatives and libertarians who squealed incessantly about the “Deep State” will make plenty of the excuses for decades of Trump’s residual troublemakers.

Although the gains from mergers and special deals might benefit consumers initially, once competition is removed the drive for profits leads to price increases.

Biden actually did some of this but sadly he was too mentally gone and his people too indifferent to economic reality to publicize it. If the American people were really aware of what some of Biden’s people were doing, they still might not have voted for Biden—he was clearly unfit for office—but that might have forced Kamala Harris to embrace antitrust as the core of her campaign (rather than “Joy”) and given her an actual reason to run.

The causes of the lack of respect for rule of law that we cited in Part 2: Side effect of the creeping lawlessness of empires? The expansion of secretive intelligence agencies? The counter-culture of the 1960s rejecting laws that required young men to be drafted to serve in an undeclared war in Vietnam? Libertarians rejecting the rule of law to smoke pot? The religious right never accepting the secular origin of our constitutional order? To this we should add unwillingness of the executive branch to enforce laws they philosophically opposed.

Some might find it grimly amusing to watch the libertarians and neoliberals who swoon at the beauty of markets reflexively defend everything that sabotages those markets.

Generous only to a point. If you’re too generous others will see you as a sucker who won’t be reliable down the road because you’ll be poor or too easily manipulated. If you’re too stingy others won’t want to rely on you because you won’t help them if the chips are down. Here’s a discussion of other aspects of village life.

The oldest coins are from Lydia around 650-600 BC where Herodotus says coins were invented.

The coining of metal was an event. When Athens discovered a new, rich silver vein in Laurion in the 6th century, the citizens voted to use the silver to pay to build 200 warships. This became the Athenian fleet that defeated the Persians and created the Athenian empire. Well, what the Athenians created wasn’t originally an empire. As their ships liberated the Greek cities under Persian rule, those cities joined the Delian League. Their ships and crew served with the Athenians in the liberation of other Greek cities. However, many liberated cities once the front lines were far from their own shores opted to substitute cash payments to the treasury in Delos in place of actual ships and sailors. By 454 BC almost all the ships were Athenian. So the Athenians simply moved the treasury to Athens and started using the money to build temples. Since the league members had given up building ships of their own they had no military means to stop this, contributions became tribute, and the Delian League became the Athenian Empire.

The first was between the federalists and the antifederalists.

For amusing portrayals of this conflict, here is a pro-Hamilton version, and here is a more balanced version.