The Third Time

Part 7 of Welcome to Charlottesville, a weekly visit to a town, a failed art project, and the future of America. (I'm still rewriting this; it's sort of a hot mess.)

Heading Out of Town

If you are lucky enough to have lived in Paris as a young man, then wherever you go for the rest of your life, it stays with you, for Paris is a moveable feast.

—Ernest Hemingway

Charlottesville, it’s just like Paris if you squint your eyes!

—Tom Coash

The third time I moved to Charlottesville I was 24. I’d finished college, dropped out of grad school, driven limousines in Daytona Beach, and worked construction in New York City. I’d learned to play guitar and write songs, and I liked my songs, but I didn’t like my singing and got too nervous performing in front of people, so I thought maybe I’d move to Nashville and become a songwriter.

Or maybe not. I was at a point in life where I wanted there to be a point to life but there didn’t seem to be one. And it wasn’t just me. That was a strange period in Charlottesville (and maybe the whole country?) when it was easy to get jobs but the jobs didn’t pay very well, and rent was cheap and college tuition cheap enough that college loan payments weren’t as onerous as in later years. So I knew a lot of people who sort of floated, taking service or sales jobs even after graduating from high-end schools like UVA.1

Speaking of which, my high school friend John Schnatterly and his friend John Quinn had just graduated from college, and found a 4-bedroom apartment on Raymond Avenue for rent. Meanwhile my brother Bret, then employed as a surveyor, worked on a site with a contractor who framed houses and was looking for help. So I found myself with a place to live and a construction job.

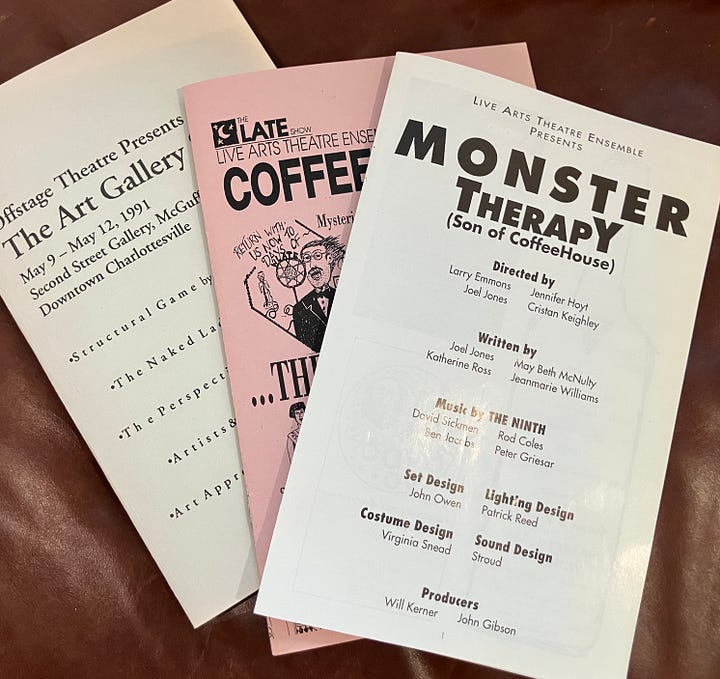

When one of my former high school teachers recommended me for a job teaching “emotionally disturbed” kids I quit construction excited to be someone who would make a difference in the world, but it turns out “restraining” kids was a major part of the job, and it gave me too much of an adrenaline rush; I was afraid I’d become a bully. So I headed overseas to busk in Ireland. This would overcome my anxieties where no one could see me, and would give me time to figure out what to do. Busking in Ireland didn’t fix my anxieties and all I figured out was that I hadn’t arranged by finances properly, so I came back stateside in 1989, still with no real direction, and here I discovered that John Quinn was part of a new theater company called Offstage Theater.

Into the Beautiful Haze

Offstage Theater was founded by Doug Grissom, Mark Serrill and Tom Coash to produce “site-specific” shows (plays staged where they were set). I saw their second production, a one-act set in a park and performed in Lee Park by John Quinn and another John named Chapin.2 Quinn now invited me to share the apartment in his parent’s basement for very low rent, and I landed a job at Crutchfield working the Customer Service phones. I started taking evening drawing classes at PVCC taught by a sculptor named Brian Maughan.3 I liked the way my mind went into a calming haze when sketching, and this gave me confidence that playing the guitar nervously had not.

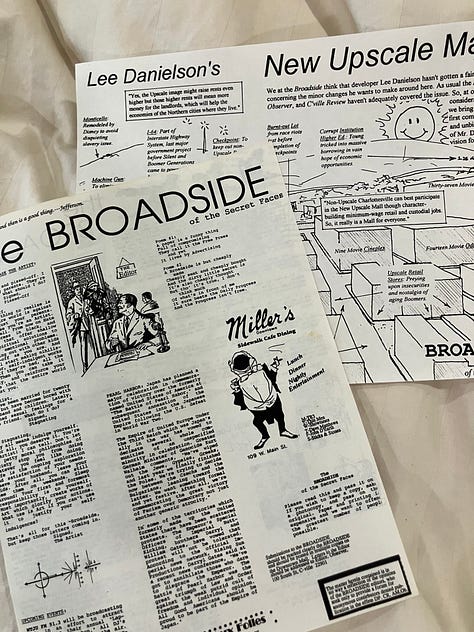

Quinn had became Resident Director of Offstage so there were piles of submitted scripts lying around the apartment, and I started to read them and mostly they weren’t good, and I thought, I could write a better play than this. I had been very involved in theater in high school but while I loved the idea of live stories, I didn’t care much for the culture, the long rehearsals, the director’s vision, the worship of acting. Then I found a book on John Quinn’s shelf called The Empty Space by Peter Brook that seemed to agree with me. In the winter of 1990 I especially loved an Offstage show consisting of locally-written one-scene plays set in a bar and performed in Miller’s downtown with the inspired name of Barhoppers.

I started helping out, running sound for of Krapp’s Last Tape in a carpet store that March, acting in a small part in a show that summer. In the fall I moved to Lovingston, Virginia (A co-worker was renovating a house and invited me to live for free if I would help.) but often would hang out at Miller’s when Quinn was tending bar aand pitch ideas for comic scenes and scripts. That winter for the second annual Barhoppers, I submitted a short play called Perfect Guy and it was staged in March, 1991. Quinn directed it, and it was great.

Dancing in the Beautiful Haze

From then on it was an avalanche. I had a couple of sketches in a “Coffeehouse,” a show format by another group called Live Arts who had recently opened a performance space in the Michie Building on Old Market Street. Then plays in an Offstage show, my own new apartment on South Street, more in the fall, sketches in another Coffeehouse, a touring show produced by Larry Goldstein, and on it went.

And I wasn’t the only newbie to find a voice in this little scene. Many people started acting, directing, producing, and writing. Adding to the fun most of these theatrical shows got reviews and media coverage so we all could read about ourselves and debate our writing, directing, and performances.4

Many of us left and came back. I took a rough draft of a novel to work on in Prague where I taught English in 1994, and spent time in Boston and San Francisco, where I wrote a rough draft of another novel. I ran the Live Arts LAB. for a year (Their smaller theater), ran Offstage for a couple of years, acted, directed, produced, eventually wrote reviews for the C-ville Weekly, and eventually even played some music gigs at Miller’s where I didn’t shake quite as much as I had a decade before.

None of this paid well, and most didn’t pay at all. I kept body and soul together with various part-time jobs and brief periods of full-time work. Thanks to Crutchfield (where I moved to sales), Market Street Wineshop, Orbit Billiards, Miller’s, that Higher Grounds convenience store (I forgot the name), and Sprint Cellular among others!

You Should Have Been Here Before People Like You Showed Up

From the time I left Lovingston my memories of the area are pretty fixed on a patch from the mall, to Belmont, and sometimes the Corner. There was the Prism Coffeehouse too, which Fred Boyce had been running since around the time Offstage and Live Arts were founded.

Throughout those years the mall got busier and busier. In 1991 I could walk up and down the mall on a weeknight and see only one or two other people. By 2001 there were people out every night. Most of the businesses seemed to do well; certainly the bars and restaurants did. It felt like a thriving community.

I finally finished a novel, House of One, and after shopping it unsuccessfully for some time, my friend Matthew Farrell published it on his indy press. I wasn’t happy with the book or with the years I’d spent trying to make it good.

The dynamism of the scene in the early 90s had imagined some sort of eventual professional success for all of us, but by the early 00s that was obviously not going to pan out. Live Arts was very active and successful, but had long moved away from the “Live Arts Theatre Ensemble” dream of paying actors, and they weren’t really producing original work as any part of their core programming. Organizations like Offstage and The Prism worked whenever people sweated and bled to make them work but there was no realistic model for their working any other way.

Throughout all these years, I rented lots of apartments, fell in love a few times, had a couple tragic romantic affairs, and lived with someone. I learned to cry, and saw a therapist, and bought and sold a house. I was immensely grateful for the chance I’d had in Charlottesville; to write plays and see them put up in a matter of months or weeks was a gift no MFA program in the country could offer. But at the same time I felt a frustration that Charlottesville had trained me and I couldn’t figure out what I was supposed to do with the training. I certainly didn’t know how to integrate all this into a family or stable career. It felt like all around us was something great but there needed to be next steps but no one knew what those could be, and worst of all, there was no way to even talk about what those could be.

I moved to Staunton just to get some distance and fresh faces and think about it all.

Woulda Shoulda Coulda

Back in the 90s a lot of older people talked about how great things were the 60s, and it irritated me, so I hesitate to talk about this little 90s art scene too much. But Welcome to Charlottesville is about cities and change, and the little 90s art scene is an important window, a snapshot of possibilities good and bad.

Things that help create an art scene: cheap real estate, downtown pedestrian mall, creative people, the free clinic, a nearby university.

Things that don’t help create an art scene: sophisticated fundraising, millionaires, people wanting to hook up, parking.

First, I witnessed enormous change.

The downtown part of the town changed radically in just a few years, and it was largely deliberately schemed. People involved in all of this would sit and talk about what Charlottesville needed and what would bring people downtown. Among other things THEATER became a normal part of a small city’s life for what might be the first time since Vaudeville.5 If people can make THEATER matter in the United States of America, people can make anything matter. I am not a rainbows-and-daisies sort of person, but I can never be pessimistic about the ability of cities to transform themselves after seeing with my own eyes a bunch of slackers feed off one another to create excitement, beauty, and meaning. We didn’t know what to do with the change, but the change happened.

Second, people aren’t motivated by money.

I’ve never seen people work harder than they did for free.

Mostly, that’s a good thing—often a very good thing—because it means people will be willing to do creative things, think, imagine, try. Nothing truly new or original is going to be compensated right away, and much that is truly new and original will never be compensated.

But it’s bad too because without investing in people—people investing in themselves really—it’s hard for things to build. People can’t stay in it long enough to learn lessons and pass them on, so each age group has to rediscover the wheel, or doesn’t rediscover the wheel, and eventually the creativity and joy fades.

I said above, “It felt like all around us was something great but there needed to be next steps but no one knew what those could be, and worst of all, there was no way to even talk about what those could be.” This experience was what got me noticing what I wrote about here. The Charlottesville art scene could only talk about aspirationally about beliefs and values, and never could broach the self-interest of the artists themselves. We never said, It’s bad for me for this organization to be doing things this way. The best we could do was say, This organization should do this because organizations should do this. Leaders, when they tried to get money, turned to fundraising culture and grant culture, and that seemed to lock in the values framing all the more. It just reinforced the notion that humans exist for institutions rather than institutions being here for humans.

The result was money for buildings, administration, and management, not creative people doing creative things.

Third, romance sex love marriage.

There’s nothing more disgusting than the rest of you having sex.

So I’d rather not talk about this at all, but it needs to be said.

The first group of leaders and doers were almost all people who were in relationships (often married), or wanted to be in relationships, or were in some cases coming out of a relationship (often a marriage), but they were not players. There was hooking up, and there was a romance to people out in public doing things together and experiencing things together—besides watching teevee. Not Hallmark or Hollywood romance, but still beauty, newness, crushes, excitement, jealousies, love real or imagined, dating, breakups, and sometimes marriages.

But then the players come. In some cases non-players became players—and that rarely ended well. From what I’ve seen decadence creates jealousy and inequality and unnecessary suffering. Rules often make us frustrated and lonely, but frustration and loneliness are actually inspiring. Decadence from what I’ve seen isn’t. The freedom of the city is to participate in making the rules that we follow. Decadence is an absence of rules which leaves us all powerless.

Probably in a town this size the best we can do is romance, sex, love, and marriage, more or less in that order.

A community is made by people doing things together.

You can create a temporary community by getting people to fear a common enemy. You can create the appearance of community by getting people to believe some shared ideology through propaganda and ritual. But to create a longterm community you need shared actions—working together, living together, solving concrete problems together.

Our little art scene did that up to a point. It was a real community. People were working, living, and solving problems, but the problems were only logistical problems. A community can’t last if people can’t marry, raise children, and grow old within it.

I think that 90s-00s Charlottesville like many scenes was not sustainable because shared our actions were too fleeting, our organizations too values-oriented, and the decadence too easy.

By that time there were some UVA alumni in New York who had formed a production company called Third Man. They were regularly producing short scripts of mine and eventually a full-length, and that gave me hope that others might want to as well. I had some friends from Prague and Charlottesville living in the city too. One Charlottesville friend was leaving his Williamsburg apartment for a year of grad school and wanted someone to sublet.

So I moved to New York City in 2004.

I wouldn’t move back to Charlottesville again till 2011 when I was married with a child of my own.

Thanks for reading Blame Cannon! This has been Part 7 of Welcome to Charlottesville. Here are the sections in order: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6. Here’s the explanation. New chapters come out every Tuesday. Part 8 will approach the end of the Police Stories project.

Please subscribe and share!

Comments are welcome but please no personal insults or profanity.

Douglas Coupland’s novel Generation X and Richard Linklater’s movie Slackers were about people in this age cohort drifting in this way.

I knew a shocking number of Johns and Davids. In fact, one thing interesting about this time was that it was the most creative scene I’ve ever come across and almost every guy had ordinary first names: John, David, Mark, Matthew, Fred, Steve, etc.

I googled Brian to check the spelling of his last name and discovered that he passed away in Yellow Springs, OH in 2020. He’d left Cville in 1997 and moved to Ohio in 2006.

Hawes Spencer founded the C-ville Review in 1989, the same year as Offstage. The Daily Progress and Charlottesville Observer also ran reviews and articles. Clare Aukofer and Barbara Rich were the major reviewers.

Asheville, NC, and Athens, GA had vibrant 90s art scenes too, but in neither was theater a big part.