Cville Grows & Separates

The Curse of the New South. Part 9 of of Welcome to Charlottesville, Blame Cannon's weekly visit to a town, a failed art project, and the future of America.

The Time Without a Name

So we’ve come to the period which in my opinion is the most important in U.S. history, a period that anticipates much of the story of Europe after WWI. I believe America, far from being a laggard in world affairs, has been the harbinger of them for a couple of centuries. The Civil War in America was the first total, industrial war, anticipating WWI in Europe, and the violent, roiling political movements in the half-century after the Civil War in the U.S. anticipate the violent, roiling political movements in the half-century after WWI in Europe.

In the rest of the country this era is often called ‘The Gilded Age,’ and has been written about a lot, but in the South it doesn’t even have a real name other than ‘The New South’—a propaganda term invented by an Atlanta newspaper editor in 1874.1 So that’s the subtitle above.

Reconstruction

Charlottesville surrendered to a Union Army on March 3rd of 1865. Many of the new citizens—former slaves now called freedmen—left the area to look for spouses, children, and friends who had been sold to other places, or simply to go to larger cities. Freedmen who remained bartered wage agreements and stayed in the area as paid workers. In April the Confederate government surrendered and dissolved, officially ending the Civil War. Reconstruction began,2 the period when the states of the former Confederacy were under military rule.

For Charlottesville that meant a series of U.S. Army officers who commanded the local garrison and the new Freedmen’s Bureau.3 These officers were judge, jury, and magistrate all in one, although local courts and town officials continued to go about their work. The Federal officers report the town as peaceful and local accounts present the federal officers as tactful, sensible, and capable. Most of the conflicts the bureau dealt with were fights over the new wage agreements—who owed what to whom—plus petty thievery and high family desertion rates expected in the aftermath of wars. Contrary to the picture presented in books like Gone with the Wind and accounts of Reconstruction I learned as a boy in South Carolina schools, there doesn’t seem to have been much lawlessness or chaos. At least not here. There is no record of any local Klan or any lynching in this decade.4

In the spring of 1867 the “Radical Republicans” with control of the U.S. Congress and took over Reconstruction from the executive branch. They standardized the military districts, charged the Freedmen’s Bureau with ensuring blacks could vote, and created rules for states to be readmitted to the Union: (1) accepting the 14th Amendment and (2) the right of freedmen to vote. They also created the “test oath” which banned those who had served as senior officers and officials of the Confederacy from voting or serving as town and county officials.

This left state politics dominated by two factions: Radicals supported federal policies while Conservatives opposed them. It’s important to note that conservative opposition did not mean segregation or explicit white supremacy. (That would come later.) Most blacks supported the radicals while whites tended to support the conservatives, but since there were about equal numbers of whites and blacks this gave the radicals a slight advantage.

In the November 1867 elections for a new constitutional convention the area nominated James Taylor, from Charlottesville, a black radical son of Fairfax Taylor; and C. L. Thompson, a white radical who lived in the County. But even the defeated Judge Alexander Rives, the Conservative candidate, had himself once been a Radical and in a later court case ruled that blacks could not be barred from juries, so there are no active factions yet arguing for segregation. It is at this point, however, when the local conservative paper, The Tri-Weekly Chronicle, began overtly race-baiting, shifting from a paternalistic tone to an insulting, dismissive tone, and appealing to whites for solidarity. The other local papers did not do this (yet).

Mid-1868 delegates in Richmond finished a new constitution. Conservatives accepted blacks voting and serving on juries, and radicals accepted ex-Confederates voting and serving on juries. On this basis President Grant and Congress in 1870 allowed the Virginians to reenter the Union. Reconstruction was over in Virginia.5

Locally radicals and conservatives remained fairly evenly matched (Horace Greeley beat Grant in 1870 by 16 votes), and blacks continued to vote in local elections, without the violence or opposition characterized by other parts of the South, up until the turn of the century.

Public Schools

Slavery had been a system of subjugation, not separation. ‘Master’ and ‘servant’ (In the Charlottesville area slaves were usually called ‘servants’.) lived in almost constant contact. The first shift to separation, was in the schools.

Public schools had never existed in Virginia. Jefferson and others had tried to start them but the bulk of the planter class, who dominated the government, always blocked these efforts.6 But after the Civil War schools were started for the newly emancipated slaves. The first such effort in Charlottesville was in 1865 by a Yankee schoolmarm, Anna Gardner. Local black families worked to support these efforts, eventually hiring teachers.

In 1867 under Congressional Reconstruction a system of Freedman’s schools expanded across the state. Petersburg and Richmond created their first ever public schools for whites to match these, but that’s about all that was done until the following year when the constitutional convention authorized for the first time in Virginia history a statewide system of free public education. Conservatives, whether converted or pretending to be, joined the radicals in approving this.

William Henry Ruffner, the newly appointed state superintendent of public instruction, presented a detailed plan in a bill to the General Assembly of 1870. Ruffner’s plan was to segregate schools. Essentially the state would take over the freedman schools, which were losing funding with Reconstruction officially over and the aid societies pulling out, and add a set of schools for whites. Black delegates objected on 14th Amendment grounds—but were defeated 19 to 80—and ended up voting against the final bill as their only means of protest.

In November of 1870 Charlottesville and the rest of Virginia opened public schools. City schools were one of the county’s districts, since although Charlottesville had been laid out with a city grid to be the county seat, the county was the basic unit of government in Virginia.

Readjusters

It turns out schools were expensive, and when Conservatives took control of the legislature in the elections of 1871 they passed a ‘Funding Act’ that gave the debt precedence over schools, roads, and public services.

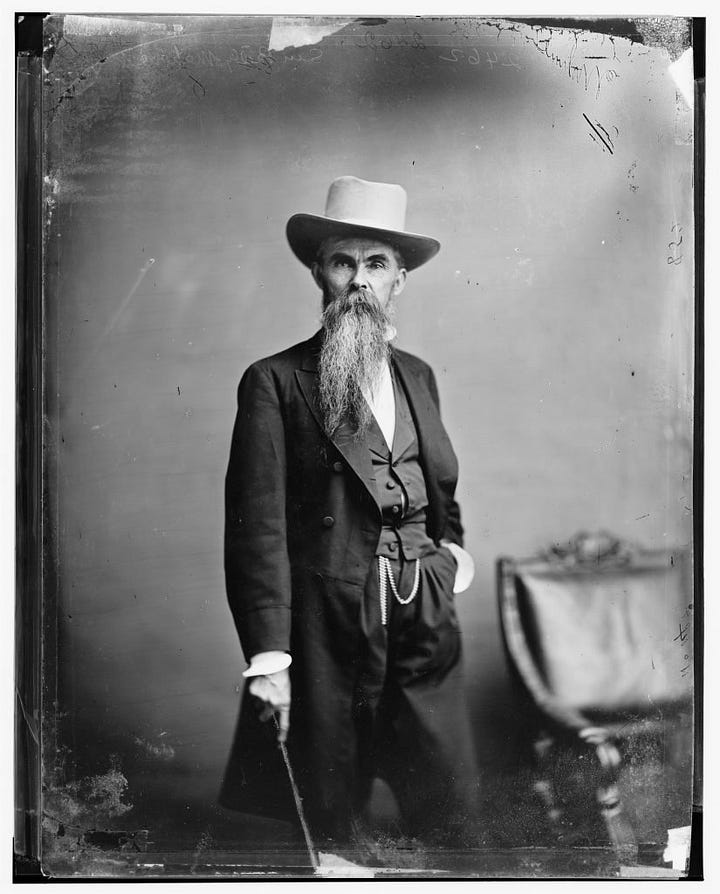

John E Massey, the owner of Ash Lawn—called Highland when it was the home of President James Monroe—got elected to the House of Delegates in 1873 and proposed anti-funding legislation to bump debt repayment below other concerns in the state to-do list. His motion failed, but the idea spread eventually collecting a mix of Radicals, liberals and reformers that became in 1879 the Readjuster Party.

The Readjuster Party was a fusion party—which is what bi-racial parties were called in that period in the South. In the deep South there were enough black voters for the Republicans to compete on their own, but in the middle states like Virginia and North Carolina, once Reconstruction ended the radicals needed allies to take on the Democrats. So under the leadership of former Confederate General Billy Mahone the Readjusters united blacks, farmers, and the rising middle class to win the legislature and the governorship in 1881. When they finally passed a version of Masey’s anti-funding bill, they lost some of the glue that held them together, but they continued to control the state until the eve of the 1883 election.

This was a period throughout the South when race-baiting was becoming more prevalent in print media whenever Democrats were frustrated with their lot. A group of business owners in Danville published a race-baiting screed against the bi-racial Readjuster government of their town. This came to be called the ‘Danville Circular’ and was reprinted in newspapers across the state.

A Readjuster politician was publicly speaking against it to a mostly-black crowd a few days before Election Day when a white Democrat was walking by and tripped over a black man, which led to accusations, punches, retreats, friends, friends with guns, black and white police officers trying to calm things down, a white militia captain showing up to command a black police officer (who wasn’t under his jurisdiction), and finally a white Democrat stepping out just as other white bystanders opened fire. They shot the white Democrat and several black men. The death of the white Democrat became proof that black people must have also been shooting, which was the excuse for white militia to come in and clear the streets of blacks. White militias in other towns and cities acting on fears and rumors did the same, and kept blacks off the streets in enough jurisdictions through election day ensuring that the Democrats swept statewide office.

The last impact of the Readjusters on the Charlottesville-area came when the last Readjuster governor, 1882’s William E Cameron, replaced UVa board and staff. They converted the university from the British system to the modern (German) system with the approach to majors and programmed years that we associate with colleges.

The City Begins

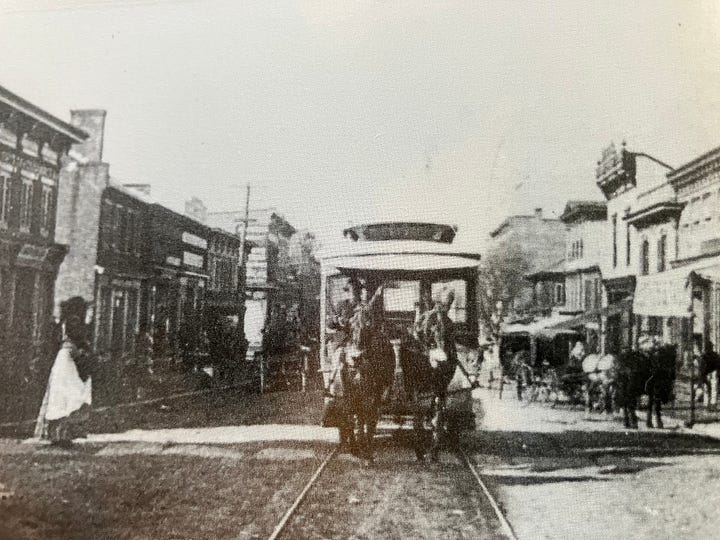

While state politics was teetering on collapse, the city was beginning to thrive. The 1850s arrival of the railroads made Charlottesville a different place, a place increasingly of coal-, gas-, and oil-powered machines. Machines are often called labor saving devices, but coal-, gas-, and oil-powered machines don’t save labor, they spread it. Six hours by train goes much farther than six hours by horse. A steam printing press prints much more with the same effort as a hand press. Woolen Mills made textiles at a rate vastly higher than the same number of people working the same number of hours. Gas-, coal-, and oil-powered machines in the late 18th century simply did more and made more per person than humans, oxen, and horses had in ages passed. Machines didn’t lead to more leisure but it sure led to more stuff. And the advantages of a city grid with machines made cities a place people wanted to be. Even small cities like Charlottesville, where the population doubled between 1880 and 1890.

It was easy for people in this era to see it as one of progress:

The first gasworks was owned by Charlottesville as a public utility by 1876, though its use was mostly limited to streetlights.

Telephones were demonstrated at the Town Hall in 1878, with working exchanges arriving in the 1890s.

A voluntary fire department was formed in 1881. (Members excused from jury duty.)

Water works got underway in 1885 with Ragged Mountain for a reservoir.

Running water is especially a big deal. That water system, including issuing bonds, trenching, and pipe-laying were all completed so it was working by mid-July. The materials were brought in by rail, but most of this work was done by hand and mule. Can you imagine building a water system today in 6 months?

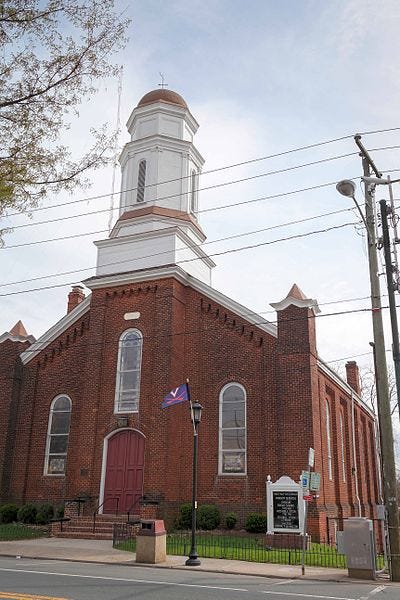

1880 Catholic Church built.

1882 Jewish synagogue built.

The first round of post-Civil War banks had folded in the Panic of 1873. But the next round of banks after innumerable renamings, consolidations and repurchases are still around today.

The Levy family, who saved Monticello and built Belmont, bought the Town Hall (built in 1850s) and opened the Levy Opera House in 1887.

In 1896 the trolley was electrified. (I don’t know how the electricity was generated. The gas works?)

In 1896 William Hotopp erected Jefferson Auditorium.

So until a fire in 1907 destroyed the Jefferson Auditorium Charlottesville had two downtown theaters.

Finally, in February 1888 General Assembly acknowledged what we have known all along, granting a municipal charter to Charlottesville so it might become an official, legal Virginia city. The charter created a government with a mayor, council of 10, and various officials, and began the untangling of city and county facilities and properties.

White Supremacy & the Curse of the New South

Meet T. McCants Stewart, a black journalist writing for the New York Freeman, taking a train in 1885 South to the state he had escaped from after the war.7 He is investigating the South for signs of mistreatment of blacks. He noted the train was not segregated in any way. Twenty-one miles below Petersburg he entered a station dining room and took a seat at a table with white people:

The whites at the table appeared not to note my presence. Thus far I had found travelling more pleasant… than in some parts of New England.

He continued south reporting no problems of any kind and in fact white people engaged in conversation more than he was used to in the North.

For the life of me I can’t ‘raise a row’ in these letters. Things seem (remember I write seem) to move along as smoothly as in New York or Boston. If you should ask me, ‘watchman, tell us of the night’… I would say, ‘The morning light is breaking.’

I am not in any way writing these things to say that Virginia was some sort of post-racial paradise. At the end of my last history post I noted how white supremacy was already in circulation as a concept, and I mentioned race-baiting above, but at this point no one close to power was openly arguing for stripping blacks of voting rights altogether or ruling Virginia forever as a one-party state, and segregation wasn’t some ancient folkway during slavery or in the thirty years since.

Thomas Staples Martin is credited as the primary agent in changing that, but he liked to work behind the scenes. He was a Scottsville native who became a lawyer after the Civil War, and took up work for the railroads through which he became connected the the Democratic party. In later years he lived in Charlottesville as well. When the Democrats swept the state after the Danville riots, Martin joined the party’s state central committee. From there he made himself Senator and oversaw what came to be called the Martin Organization which funneled bribes from the railroads to candidates who were struggling with campaign contributions due to the economic recessions of the 1890s.

Under Martin’s behind-the-scenes-leadership the Democrats decided not to let fusionist parties happen again, so in 1894 the General Assembly passed the Walton Act. This mandated secret voting, which sounds like a good idea, but it also authorized the appointment of ‘special constables’ to read all the ballots, and these were appointed by the currently-ruling Democratic party with no oversight. The Democrats also went in for Karl-Rove-style voter roll purges and redistricting.

The pushback against all this led to a state constitutional convention in 1901, but since the Democratic special constables controlled all the ballots the delegates ended up being 88 Democrats, 11 Republicans, and 1 Independent. Their idea of reform was to go further. It took them a year, but borrowing ideas from Louisiana, South Carolina, North Carolina, and elsewhere they came up with the Constitution of 1902 which effectively erased the black vote. It combined a poll tax with an understanding clause (a politically-appointed white registar would judge how well a prospective voter understood the constitution), and Confederate veterans and their sons were exempt.

Following a decision of the Virginia Supreme Court the Constitution of 1902 simply became the law of the land. Voting declined precipitously, as intended, and although about 15,000 black citizens still managed to vote after 1902, this was too small a group to impact state politics.

Enter The Long Night

With that bit of bureaucratic wrangling one-party rule descended on the state for more than a half-century. Political appointed registrars counted the general votes. Candidates were decided in closed caucuses. The Democrats managed to do away with democracy entirely. It was all closed, it was all settled, and would remain so.

Much of the vitality and dynamism of Charlottesville and the state was replaced by the Lost Cause mythology, a new movie-inspired Ku Klux Klan, eugenics and pseudo-scientific racism against blacks and Native Americans, lynching, and new forms of segregation year by year. Segregated passenger trains, then segregated streetcars, then segregated restaurants and hotels, and finally in the 1910s segregated housing.

Weirdest was that starting in the 1890s commentators, courts, and sociologists in the South and North began to claim that segregation was an ancient folkway that couldn’t be changed by law—even as these folkways were being created by law bit by bit right before everyone’s eyes. It was all propaganda, the corruption of the 80s & 90s Democrats was projected backward on the ‘Reconstruction governments’, the pretense of custom as king, and today every encyclopedia, book, article, and activist that lazily claims that Reconstruction ended and Jim Crow began immediately after, erasing the thirty years in between, continues that awful scam.

By the time housing in the South began to be segregated the next major change in city life had begun: Henry Ford’s Model T began production in Detroit in 1908. This was the first affordable mass-market automobile, and would gradually transform the physical environment as the locomotive had before.

Thanks for reading Blame Cannon! This has been Part 9 of Welcome to Charlottesville. Here are the sections in order: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6, Part 7, Part 8. Here’s the explanation. New chapters come out every Tuesday. Tuesday 9/10 will tell the thrilling story of my fourth time moving to Charlottesville.

Please subscribe and share!

Comments are welcome but please no personal insults or profanity.

Named originally for Lincoln’s proposed Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction, which was countered by Congress with the Wade-Davis Bill, which in turn was vetoed by Lincoln. Back and forth it went until Radical Republicans got a working majority in Congress and took over Reconstruction in 1867.

Officially the Bureau of Freedmen, Refugees, and Abandoned Lands created in March, 1865. It’s local appointees descended in rank as Charlottesville proved to be easy to govern. A Lieutenant Colonel in May; a Captain in June; after that Lieutenants.

When lynching did happen it was very much written up in local newspapers. There was a lot more lynching in the state after the 1890s when the Democrats took up more overt White Supremacy.

Reconstruction ended elsewhere in the South as part of a nasty political deal. A deadlocked presidential election was thrown into the House of Representatives, and Southern Democrats agreed to switch sides, abandon the (non-Southern) Democratic candidate, and support Republican Rutherford B Hayes, provided the Republicans would withdraw federal troops from the South. Which the Republicans did. This also more or less buried the abolitionist wing of the Republican party. (The Republican party had been founded largely in an alliance between abolitionists and industrialists and at this point the industrialists took over.)

Virginia still had a property requirement for voting until the 1850s.

The Strange Career of Jim Crow by C Vann Woodward, pg 39.