Violence & the Freedom of Cities

The UnitedHealthcare CEO assassination took place in an urban area because only in urban areas can people get face to face with their enemies.

Where the Killings Happen

We’ve all heard about the killing of Brian Thompson, the UnitedHealthcare CEO, gunned down in New York City as he was entering the New York Hilton Midtown on 54th Street between 6th and 7th Avenue. Vast numbers of Americans have shed few tears for Thompson. Many, perhaps most Americans, feel that he got what’s coming to him.

A man named Luigi Mangione has been arrested for the charge.1

One thing I haven’t seen anyone write about is the fact that Brian Thompson was shot on a city street. He was shot there because cities and urban environments are the only place where the rich and powerful can be gotten at by those who hate and fear them.

But first why might Brian Thompson be hated and feared?

American health insurance companies are famous for putting sick people and their families through a cruel gauntlet of denied claims, impenetrable bureaucracy, and officious delays—all to serve greedy CEOS and their vampiric stockholders. United Healthcare was one of the largest and worst.2 It had the largest claim denial rate of any health insurance company and it is part of a veritable Chthulhu of billing services, conglomerates, sub-conglomerates, and leveraged service providers. Here’s how Matt Stoller describes it on his substack:

Take one of the first antitrust suits brought by the Biden Justice Department, which was actually against UnitedHealth Group, because that company was trying to buy Change Health, the dominant payment network for hospitals and pharmacies, kind of like Visa/Mastercard in health care. The argument was that UHG would misuse the data that flowed over its wires, to surveil its customers and rivals.

The judge, a conservative Republican corporate type named Carl Nichols, wrote a stinging rebuke of the Department of Justice in 2022, ruling in favor of UnitedHealth Group. After Nichols cleared the merger, of course, disaster ensued. Change Health’s network got hacked and stopped working for more than a month, leading to cash crunches at hospitals, doctor’s practices, and pharmacists. Ninety-four percent of hospitals, for instance, were affected, and roughly 40% had more than half of their revenue affected by the hack.

So there are a lot of motives for why he was killed, but what about where he was killed?

Cities, Crime, and Political Violence

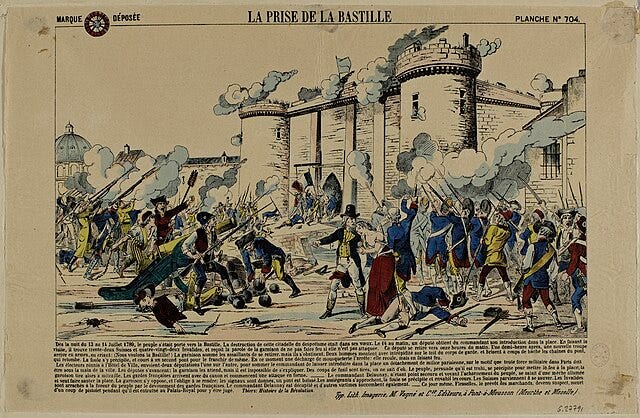

Since ancient times revolutions in political rights have taken place almost exclusively in cities. In cities social classes can battle for a voice in the government because the rich and powerful aren’t able to withdraw from everyone else as they can on rural estates or palaces. In public streets anyone can be tarred and feathered, lynched, or just shouted down by an imprompu mob.

This threat is essential to the basic freedom of cities. The natural freedom of a rural area is the freedom to be left alone. The natural freedom of an urban area is to participate in making the rules and laws that bind the community together. (Remember that before the automobile almost everyone was either rural or urban.3 )

Before the automobile the rich and powerful might prefer the safety of landed estates, but often they put up with the risk of cities for the power, wealth, opportunites, and culture the city provided. Where the rich and powerful stayed out of cities, the cities could developed a degree of autonomy that made them a political force that could eventually side with the centralized authority to attack the rich and powerful. Where the rich and powerful remained in cities their property and their institutions could be attacked, and they could be tarred and feathered, or lynched, or just shouted at.

Assassinations like that of Brian Thompson are the ultimate threat. Potential assassins can use the crowds to get close to their targets. Sometimes—as in the case allegedly of Luigi Mangione—they can evenescape into the crowd after. Abraham Lincoln was murdered in a theater in Washington, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was murdered on a street in Sarajevo, and Tsar Alexander II was murdered on a street in St Petersburg.

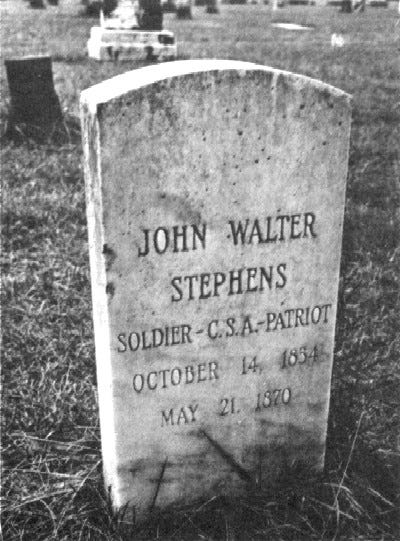

During the first Gilded Age (I’m counting our own time as the Second Gilded Age) robber baron James Fisk was assassinated in New York and Henry Clay Frick in Pittsburgh.

There was a whole slew of worldwide anarchist assassinations and bombings in the late 19th century. These took place invariably in cities.

But however satisfying the revenge in gunning down a hated figure, most assassinations don’t accomplish much.4 Yes, assassinations inspire other assassinations as school shooters inspire other school shooters, but reforms and improvements in American life, and life everywhere else, have tended to come from organized groups such as city political machines, unions, and political parties.

The powerful rarely respond to threats from below by ceding domination and control. After all, the powerful tend to get powerful because they have an overdeveloped instinct to dominate and control. When all people are threatened they tend to double down on their habits and instincts. So in response to assassinations CEOS will tend to double down on the domination and controlling. More laws, more cameras, more AI online tracking and surveillance. This tends to enrage people more, encouraging more violence.

If there ends up being a rash of CEO assassinations the surviving CEO response will be to move their conferences outside of cities, off to the types of bland office parks that are hard for gunmen and bombers to get to without being observed. They’ll drive on guarded roads from gated suburbs and office parks to airports where they’ll fly in private planes to other gated suburbs and office parks. (They mostly live that way already which is a major cause of our economic decline.)

I’d guess that future Luigi Mangiones (assuming he’s guilty) will escalate by using drones to take down private planes. That’s the clearest weakness and perfect symbol of the ruling classes.

It’s ugly stuff.

But Why U.S. Health Insurance So Bad?

After WWII the victorious allied powers believed—with good evidence—that what made communism and fascism popular were social programs. So they decided they should make a few compromises if they wanted their beloved social and economic order to continue.5

Internationally, the U.S. took the lead in creating the United Nations, NATO, and the various world economic and legal structures. The U.S. dollar would be the world’s currency, and the U.S. navy would patrol the seas, so that any country could trade with any other country. Trade would reduce the number of territorial wars. While some of my fellow lefties think of this as greedy imperialism from the beginning—and there were certainly plenty of greedy imperialists in the U.S. decision-making mix—for the first twenty years or so the U.S. was exporting far more than we were importing. (That includes many raw materials like oil.) It was in U.S. self-interest to create a system that would do well by doing good. Policing the world and letting foreign countries ship goods to us was not much of a sacrifice at the time since our economy and industrial sector were so much bigger than anyone else’s. (They were bigger before WWII, and then after the war everyone else’s industrial sector was annihilated.) So we bestrode the globe like a Colossus creating an economic and political order that worked pretty well for a few decades.6

Domestically, the allied powers created and expanded social programs to compete with fascist and communist programs, such as pensions, poverty relief, public universities, and especially health care. (After major wars a lot of people naturally think about health care.) France, Germany, and Great Britain each created their own system: Great Britain created its National Health Service, France created universal national health insurance, and Germany created a highly regulated and complicated mix of public and private health insurance that also regulated health care. (The French system has held up the best.)

The U.S., however, didn’t need to create a program from scratch. During the war the 1942 Stabilization Act had tried to prevent wartime inflation by limiting wages and this accidentally led to employee-based health insurance.7

In 1943 the War Labor Board, which had one year earlier introduced wage and price controls, ruled that contributions to insurance and pension funds did not count as wages. In a war economy with labor shortages, employer contributions for employee health benefits became a means of maneuvering around wage controls. By the end of the war, health coverage had tripled.8

Since they couldn’t increase wages, corporations—with the encouragement of unions—began offering health insurance to attract workers, and in 1954 when the IRS ruled that contributions to employee health care were tax deductible, the system took off.

Not that it’s a good system. Automobile, life, and property insurance share risks over a large pool so we can have access to a large amounts of money should we need it, but few people use these types of insurance at any one time, so it doesn’t cost anyone very much to participate. In contrast we all need health care every year.

Also unlike other forms of insurance health insurance companies are in the position of the classic middleman, able to pass on higher fees to businesses, clients, and the health care providers.

Imagine if you had to go through your home owner’s insurance any time you did work on your house. Think of how much your insurance company would add inspections, administration, and kickbacks.

Imagine you had to buy and sell your car through your auto insurance company.

Imagine you had to make lifestyle decisions by regular negotiations with your life insurance company.

Health insurance doesn’t actually do anything useful. It offers no actual benefit to the patient, nurse, or the doctor, yet sucks up 30-40% of U.S. medical costs. And that leaves aside the time and anguish of dealing with the brutal bureaucracy of health insurance companies. Think how insane it is that our payments actually pay the salaries of the people who reject our claims!

When I was a kid my family doctor had a nurse, receptionist, and a bookkeeper. When I happened to see him in my 40s (I didn’t have a doctor at the time and I needed antibiotics.) the office had the same nurse, receptionist, and bookkeeper—plus a new employee whose entire job it was to deal with the insurance companies. Think of the waste.

I’ve belabored the point enough: You can easily find online estimates of the outrageous costs of insurance companies, the tens of thousands of deaths caused by their refusal to pay claims, the stress caused by dealing with them, and so on.

Medicare for All

I wrote about Medicare for All on social media many years ago. I wanted to get arts organization, then in the thick of Black Lives Matter introspection and reform, to embrace Medicare for All for their employees (many of whom weren’t insured), audiences, and community. Not a single organization showed the slightest interest. Many people hated what I was writing. People with health insurance just don’t seem to want anyone poorer to share their doctors and nurses.

The usual excuse, Oh well, too bad, we’d love to help the poor, but it’s just too expensive, suddenly was blown to smithereens by the Covid governments of Trump and Biden who blasted money at everyone and everything when the “Market” wanted ti. Then after a couple years the Biden people worried that wages were getting too high, and that was the cause of inflation, so the money pipeline dried up. And now America with its goldfish memory is back to Oh well, too bad, we’d love to help the poor, but it’s just too expensive.

At root everyone was afraid to associate their health with anyone poorer. Our economically segregation is so extreme that Americans don’t really understand anyone lower down the social ladder, yet hope against all reason that those of higher social classes will understand them. We’ve professionalized our government to the point where it can’t really respond to public pressure yet hope that more professionalization will help. We continue to pretend that cartels and oligarchs are markets and innovators if we squint our eyes the right way.

These are not new problems. America survived the bullets and bombs of the First Gilded Age, and we’ll survive the Second. But it took a lot of decades from the anger of bombs and guns to the institutional building the creates real political power.

It would sure make things better if our national political parties would learn to govern, but my suggestion is not to wait for the state and federal level, but start locally.

Thanks for reading Blame Cannon!

Ken Klippenstein’s substack published his manifesto.

Subsidiary of UnitedHeath Group which by revenue is the world’s largest health care company and ninth largest company of any kind.

Before automobiles railroads and streetcars introduced the first limited suburbs of the modern type, and there have been a few suburbs served by ferries.

Although isn’t it better when disgruntled people kill someone powerful rather than “going postal” and shooting up the innocent in schools, businesses, movie theaters, and dance clubs?

Tony Judt’s Postwar is a great account of this period.

It was under this U.S. system that so many countries were able to free themselves from the European imperial powers, but it was also under this system that those countries gradually ended up heavily in debt.

There was employee-based health care in certain industries going back to the 19th century, but it wasn’t typical for empoyers or employees to think in those terms in job negotiations.