What about Bob?

My wife and I recently watched the Bob Dylan biopic A Complete Unknown. I enjoyed Edward Norton’s turn as folksinger Pete Seeger, and especially Monica Barbaro’s as Dylan’s lover-rival Joan Baez. Timothee Chalamet is fine as Dylan and there are some effective music scenes,1 but for me the movie fails—as music biopics always seem to—because it’s about fame not music.

According to A Complete Unknown young Dylan arrives in New York in 1961 at the height of a folk music scene. Through his powerful stage presence and natural genius he quickly finds fame and fortune and the embrace of the folk establishment. But then at the Newport Folk Festival in 1965 Dylan SHOCKS the folkies by adopting ELECTRIC INSTRUMENTS and the liberating power of ROCK AND ROLL. Only Dylan’s hero Woody Guthrie and friend Johnny Cash understand this choice. Dylan had to be Dylan, you see. Sometimes other characters are given a chance to make counterarguments and the movie lets Dylan look like the jerk from time to time, but the songs, which are what actually made Bod Dylan famous, just spring from his mythic genius brain to the amazement of everyone around him reinforcing the notion that some people just have it and some just don’t.2

So this week I’m going to take a break from person stories, prehistoric global warming, industrial civilization, and the Trump presidency to show you how an actual songwriter created actual work.

After many years and one album of other people’s music, Bob Dylan learned to write songs himself from a record called King of the Delta Blues Singers by a musician named Robert Johnson. Imitating what Robert Johnson did—not in style but in process—is how Dylan devised his breakthrough album, Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan.

I’m not a big Dylan fan myself. I like Freewheelin’ and I really loved the album that came after it, The Times They Are A-Changin’, but I was picking through New Dominion Bookshop a few years back and came across, Bob Dylan’s memoir, Chronicles. I opened to a random page and Dylan was vividly describing the same Greenwich Village neighborhood in the 1960s where in the 2000s—to far less fanfare— a theater company regularly performed my plays. So in a burst of New York nostalgia and curiosity about New York history, I bought Chronicles and read it over the next few days. Like most Bob Dylan it mixes incisive observations and honest revelations with gobs of meandering nonsense, but it was worth it because in the final section Dylan describes listening for the first time to King of the Delta Blues Singers. My friend James Bowers introduced me to King of the Delta Blues Singers in high school, long before either of us heard a full Dylan ablum.3 But Dylan and Johnson are so different in sound and style, that later when I did listen to Dylan albums I never made a connection. But reading Dylan’s description of what the record meant for him, I felt like I understood Dylan through Robert Johnson, and Robert Johnson through Dylan, and that’s an experience I’ll try to share with you.

A lot of people hate Dylan for good and bad reasons, but whatever you think of him I hope you’ll find this story interesting. Popular music is a big part of American culture, and this is the rare case where we can really see where it comes from, and why Dylan’s songs and career are so different from the songs the rest of us write. (And the careers the rest of us have or don’t have.)

Plus the story even has a brief Charlottesville angle.

Bobby Zimmerman

Bobby Zimmerman was born in 1941 in the happy, prosperous middle-class city of Duluth, Minnesota, thriving on the happy, prosperous middle-class banks of Lake Superior. Alas, when Bobby was six his father contracted polio, lost his job, and the family retreated to his mom’s hardscrabble iron-mining craphole of Hibbing, Minnesota. There dad ran an appliance store.

In high school Bobby Zimmerman formed several rock bands playing Little Richard and rockabilly tunes for contests and dances. (These bands had electric instruments. Bob Dylan was never a folk musician who took up rock; he was always a rock musician who spent five years obsessively experimenting with folk before returning to his rock roots.) His Hibbing bands kept quitting on him, however. Dylan later said that singers and lead guitarists always had better options.

In 1959 he went off to the big city of Minneapolis to attend the University of Minnesota, and there he discovered a folk scene with fascinating music he’d never heard, alluring record stores, and coffeeshops where a musician could find an audience and make a little money playing with just a guitar and harmonica. No band to quit! So Bobby Zimmerman—now calling himself Bob Dylan—started performing solo.

Whatever you think of Dylan, he always loved songs. He learned songs quickly and had a prodigious memory. Gradually he built up a huge repertoire. In Minneapolis this included songs he learned from the records of Pete Seeger, Paul Clayton, Joan Baez, and Dave Van Ronk of other folk musicians, some contemporary, some older, but lightning truly struck when he started listening to Woody Guthrie.

Woody Guthrie

Woodrow Guthrie was born in 1912 in Okfuskee County, Oklahoma, to the son of a prosperous businessman and landowner. Alas, Guthrie’s mother had a mysterious neurodegenerative condition that caused physical and mental deterioration. She lashed out violently at those around her and had a dangerous tendency to light stuff on fire. She burned the family house down before Guthrie was born (allegedly on the day after it was completed), and apparently lit Woody’s sister on fire. By the time Woody was 14 the family tragedies and stress had ruined their finances, so dad went to Texas to try to work off debts. Meanwhile mom went so crazy she had to be committed to an asylum. So teenage Woody joined dad in Texas. There he quit school and began to busk in the streets and play at dances.

Like Dylan, Woody liked songs, could learn them quickly, and gradually built up a huge repertoire. He headed with other Dust Bowl Okies to California where by the late 1930s he had success in the new medium of radio until he was fired for communist sympathies. In 1940 he moved to New York City where he became a fixture of the nascent folk scene of Greenwich Village, recording—particular the albums Dust Bowl Ballads I & II—writing songs—including “This Land Is Your Land”—and eventually forming the Almanac Singers with Pete Seeger.

Unfortunately, by the late 1940s he discovered he was afflicted by the same condition as his mother. At his time it was identified Huntington’s Chorea.4 He was hospitalized in 1956, lost the ability to speak by 1965, and died in 1967.

Bob Dylan

Bob Dylan’s singing is often made fun of, but he was trying to sound that way, because he wanted to sound like Woody Guthrie. Dylan idolized Guthrie. Perhaps partly because he identified with Guthrie’s temperament and appearance—both small, wiry men—similar in humor, style, and musical taste. So he became a sort of Woody Guthrie clone.5

In January 1961, he did what any Woody Guthrie clone would do: he went to live where Woody Guthrie had gone to live—New York City. As in A Complete Unknown, Woody arrived in the middle of a thriving musical scene. It was the second wave of the “folk revival.” Unlike the movie Dylan’s success took longer and was more gradual.6 He first got a regular gig as a harmonica player backing up the host at the Cafe Wha, while playing guitar in in other coffeeshops for tips. After a couple months he landed a regular paid spot in the rotation of the Gaslight Cafe, while continuing to pay other gigs when he got one. He became friends with performers whose records he knew and admired, like Dave Van Ronk and Paul Clayton.7 No one reported being blown away by Dylan’s performances. He was not some kind of wunderkind. But he knew a lot of songs, played with an interesting intensity, never hesitated to audition, and showed up on time. He was soon one of several dozen performers making a modest living. In the early fall he stopped sleeping on couches and got an apartment for $60 a month.

That’s about $700-$800 in modern money, which was roughly his weekly take at the Gaslight. So his “cheap apartment” in NYC in 1961 cost 1/4 of his pay and he had more than one room and was in the heart of the city. Urban rents were lower in this period than before or after because so many Americans were moving out to the suburbs.

In September Dylan was asked to play harmonica with folk singer Carolyn Hester. She was recording her third album for Columbia producer and talent scout John Hammond. Hammond dropped by a rehearsal, liked Dylan, and by chance the day before or the day after (I can’t remember which) read a positive newspaper write-up of a Dylan guest set at Gerde’s Folk City. So Hammond offered him an audition and then a recording contract with studio time booked for November.

Here too, what a different world! Newspapers regularly sent reviewers to live events and there were dozens of newspapers, magazines, and periodicals. Musicians had to play far tighter sets and show up on time—unlike today—but even beginners weren’t expected to do their own advertising, and they routinely were offered multi-record deals. Record companies could do this because an entire album could be recorded in only a few sessions, and also because the baby boom now in its teenage years would buy enough of anything with a young face on it, that the companies could break even.

Now Dylan had a couple of months to figure out what to record. At the time folksingers (and this is something A Complete Unknown gets completely wrong) didn’t write much, since their goal was to be part of a tradition, so they spent a lot of time listening to other performers, listening to records, and looking through folk song collections. To help out, the more-established folksinger, Paul Clayton, road-tripped Dylan to Virginia with Carolyn Hester and Pete Seeger’s half-brother, Mike Seeger. They played at Charlottesville’s Gaslight Restaurant on Main Street, then drove out to cabin in Brown’s Cove that Clayton or Clayton’s family owned. There they poured over sheet music and listened records and Clayton’s neighbor who knew a lot of traditional songs.8

Eventually November came and Bob Dylan recorded his album over a few days. What would be imaginatively titled, Bob Dylan, included two original songs, both heavily influenced by Woody Guthrie—one song literally is called “Song to Woody”—and eleven traditional songs, often played in the style other folksingers. Dylan’s version of “House of the Rising Sun”—later a hit by the Animals—was basically Dave Van Ronk’s version of “House of the Rising Son.” (Van Ronk was none too pleased since he had been about to record it himself.)

In March 1962 the record came out. It was pretty bad and didn’t sell much. But within a month Dylan himself was back in the studio recording tracks for the next record.

Again, what a different time! Record companies gave artists several albums before dropping them. But on the other hand record companies gave their recording artists very little studio time that rigidly scheduled. Dylan’s second album ended up using only eight sessions over the course of a year. This was before the era of multi-track recording which dramatically increases the time it takes to make an album.

Six months before when Dylan was first signed to Columbia Records, John Hammond had given him an advance copy of new record about to released. It was one Hammond was particularly proud of it since it brought to the label the work of an obscure musician Hammond particularly admired, the late Delta blues player named Robert Johnson.

Robert Johnson

Robert Johnson was born a year before Woody Guthrie two states away in the Mississippi Delta. Johnson’s family had been relatively prosperous too. (Seeing a pattern, yet?) They farmed land they owned and ran a furniture business in Hazelhurst, Mississippi. But dad ran afoul of the local white supremacists, and barely having escaped lynching, he fled to Memphis to live under an assumed name. Robert came to Memphis too where he attended school until he was 8 or 9. Then his mom remarried—this time to an illiterate sharecropper—and young Robert traded city life for cotton chopping. As a teenager he ran away and wandered the Delta first becoming a harmonica player (See the other pattern?) and then learning to play guitar in Beauregard, Mississippi from a musician named Ike Zimmerman (no relation to Robert Zimmerman, i.e. Bob Dylan).

Soon Johnson was an itinerant bluesman, performing on streetcorners, in lumber camps, and in juke joints. In 1936 he sought out H.C. Speir in Jackson, Mississippi, who acted as a talent scout for record companies. Speir connected Johnson with a recording engineer named Don Law who recorded him in San Antonia in 1936 and again in Dallas a year later. Johnson was paid cash for his efforts, several of the sides were issued as 78s by the Vocalian label and at least one sold decently, but before he could make additional recordings he died in Greenwood, Mississsippi in 1938 either of syphilis or poison.

According to those who traveled with him, Johnson liked all manner of songs, learned them easily, and had a large repertoire. (Pattern #3) Allegedly one of Johnson’s favorites was the Roy Rogers hit “Tumblin’ Tumbleweeds.” But the recording industry marketed their wares in catalogs by category. Blues songs seemed to be selling well in the mid-thirties so musicians were asked for blues. In other words the songs Johnson recorded weren’t a cross-section of what he played in public, but are what he or Don Law thought would make a popular record. This tendency of recorded music to fit in commercial genres gives us a very false picture of what music in the American South was like. To a record collector this guy plays Delta blues, that guy swing, and that guy country, but all three might have actually played similar songs when performing.

Anyway two decades years later in 1961 John Hammond, who loved Johnson’s music, proudly issues King of the Delta Blue Singers on Columbia Records, and gives acetates to various people he thinks might appreciate it, including young Bob Dylan whom he’s just signed.

The title is ridiculous. In no way was Robert Johnson a “king” of anything. Johnson was never the most popular or admired of blues singers in the Mississippi Delta at any point in his life or in the years up to the album’s issue. A man named Charley Patton had been the king if there was one. Patton was the creator of the style called “Delta blues” and was the most influential performer. Son House and Willie Dixon, who were influenced by Patton, were both better known than Robert Johnson. (They all knew each other.)

Dylan took King of the Delta Blues to the apartment of Dave Van Ronk, who was one of the stable of performers with him at the Gaslight. (The guy whose version of “House of the Rising Sun” he was about to steal.) Van Ronk knew a lot of blues, but he’d never heard of Johnson. They put it on the record player to listen. Here’s how Dylan describes it in Chronicles:

“From the first note the vibrations from the loudspeaker made my hair stand up… The songs… jumped all over the place in range and subject matter, short punchy verses that resulted in some panoramic story—fires of mankind blasting off the surface of this spinning piece of plastic…

“Johnson’s voice and guitar were ringing the room and I was mixed up in it. Didn’t see how anybody couldn’t be. But Dave wasn’t. He kept pointing out that this song comes from another song and that one song was an exact replica of a different song. He didn’t think Johnson was very original. I knew what he meant, but I thought just the opposite. I thought Johnson was as original as could be...”

What did Van Ronk mean?9 Here are some examples I’ve cued up from You Tube:

Listen to Robert Johnson’s “32-20 Blues” and then listen to a song by bluesman Skip James called “22-20” recorded seven years earlier.

Compare Johnson’s “Last Fair Deal Gone Down” with a record by white country player Fiddlin’ John Carson from many years before, “Don’t Let Your Deal Go Down.”

Here’s Johnson’s “Walking Blues” and here is Son House’s “Death Letter Blues.” Johnson knew Son House and may have learned it directly or from a record.

Some of Johnson’s songs are third-hand. His “Kindhearted Woman” is based on “Cruel Hearted Woman” by Bumble Bee Slim which was lifted from “Mean Mistreater Mama” by Leroy Carr.

Johnson’s “Come On In My Kitchen” comes from a song by the black country band, The Mississippi Sheiks, called “Sitting On Top of the World” with additional influence by Leroy Carr’s “How Long” and a version of yet another Skip James song. The Mississippi Sheiks played in the areas Johnson traveled through. So he could have learned this in person or by record.

One of my favorite Johnson songs is “Hellhound on my Trail” which I vividly remember listening to while driving in the snow at night with a girlfriend asleep in the passenger seat. Great song. Johnson’s version came from a Johnny Temple version of yet two more Skip James songs, “Devil Got My Woman” and “Yola My Blues Away.” Again, Johnson would have learned this off a record, since Temple have left the Delta for Chicago before Johnson was traveling.

There’s a certain irony in a folk musician like Dave Van Ronk criticizing one of the traditional musicians he was listening to for being “unoriginal” and certainly all the musicians Johnson borrowed from also borrowed from other musicians before them, but Johnson is doing it differently.

First, while Johnson owes a lot to Charlie Patton, Son House, and Willie Brown—musicians he knew well throughout his life in the Delta and mentions in his songs—he was equally influenced by the records of Leroy Carr and Skip James, neither of whom he ever met.10

Second, when working from records Johnson refashions his source material in unusual ways. He’s not playing hit songs as he probably did when playing on a streetcorner; he’s using tunes and ideas from records to make ostensibly different records with different titles that are often juxtaposed to the original, as if backhanded compliments or insults. “Mean Mistreater Mama” switches to Johnson’s “Kindhearted Woman.” “Sitting on Top of the World” was triumphant; Johnson’s “Come On In My Kitchen” is anxious, humble. In “Devil Got My Woman” the devil is threatening the singer second-hand; in Johnson’s “Hellhound on My Trail,” the devil is threatening the singer directly i.e. “The Devil’s Got Me.”

What Dylan learned while listening to King of the Delta Blues with Dave Van Ronk was that this eerie, haunting music was created from reworking source material in a particular way. Robert Johnson in order to make records had thought of other records that he liked and reworked them incorporating his own reaction to the material. As if I would take the tune of Johnny Cash’ “Folsom Prison Blues” and make it a song about being happy to be free from prison, or make it song about a psychological prison. Johnson isn’t just taking a tune; he’s riffing on the subject matter he associates with the tune. This gives Johnson’s music a sense of layers, almost a mythic quality that has led legions of music fans into repeated stories about Johnson’s mysterious past, and pacts with the devil, and so on.

At some point over the following months as Dylan was listening to King of the Delta Blues over and over and probably reflecting on his disatisfaction with his first record, it clicked that he could do the same.

The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan

So he did. For his second album, Dylan picked existing songs and reworked them in his own voice and style with a sort of meta commentary on the originals.

Dylan’s “Girl from the North Country” is based on the tune of "Scarborough Fair.” Scarborough Fair was in Yorkshire, England on the North Sea, and is based on a ballad tradition featuring a ghost demanding an innocent carry out impossible tasks. Dylan learned the song on a trip to England where—while separated from his girlfriend Suze Rotolo—he had an affair with a British woman from Yorkshire. So Dylan uses a song about Yorkshire to sing about a girl he met who was from Yorkshire and asks the listener not to make the girl buy land and sew a shirt with no seams but simply for the listener to make sure the girl has a coat.

Jean Ritchie's "Nottamun Town” is a song about an individual soldier experiencing impossible contradictions and blatant absurdities becomes Dylan’s “Masters of War” a song about the contradictions and absurdities of warmakers.

The tune and theme of Dylan’s “Blowin’ in the Wind” comes from a slave song called “No More Auction Block.” The link is to Dylan himself peforming it in his Gaslight sets. Instead of the end of suffering being celebrated, as in the slave song, Dylan projects the end of suffering into an unlikely future.11 No more suffering becomes How long before no more suffering?

The most original song on Freewheelin’ is “A Hard Rains a-gonna fall” based on a traditional ballad called “Lord Randall.” Dylan adds the single “It’s a-hard, it’s a-hard…” line of the chorus, and wanders more in the lyrics. While “Girl from the North Country” made “Scarborough Fair” more personal, “Hard Rain” makes “Lord Randall” more global. It’s a precursor to his post-folk logorrhea.

Remember Paul Clayton? Dylan’s more famous friend with the cabin in Brown’s Cove? Bob Dylan’s “Don’t Think Twice It’s All Right” is taken from his version of "Who's Gonna Buy You Ribbons (When I'm Gone)?” Dylan makes it sharper and probably is referencing his feelings about Clayton himself. Later on he wrote a lot of songs dissing individuals and groups he was discarding.

As if to emphasize the process, the album’s one song that is identified as “traditional” is “Corinna, Corinna” recorded by the Mississippi Sheiks in 1928—the group that was the origin of Johnson’s “Come On In My Kitchen” and other songs. But Dylan inserts not one, but three verses, from three different Robert Johnson songs.12

Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan does not imitate King of the Delta Blues in style at all, but it is a duplicate of Robert Johnson’s approach to creating songs, and the model for Dylan’s entire career. It is original, or unoriginal, in the way that Johnson is original, or unoriginal, depending on your point of view. It’s songs have that haunting, eerie quality that comes from the layers of their origins, and the internal commentary, and like Robert Johnson, Dylan’s songs and often his performances are arguably better than their sources, in many cases dramatically so.

The one reprehensible aspect of Bob Dylan, if the rumors are true, is that his estate sues anyone for approaching his material in the way he approached everyone else’s. I don’t know the truth of this, but it makes it hard to listen to Dylan sometimes. He settled out of court and paid $5000 for using Jean Ritchie’s song without giving her credit, but his estate is not likely to settle out of course and accept $5000 for anyone else using Masters of War in the same way. Again, that’s if rumors are true.

The Time It Was A-Changin’

“The guy saw things. He had an incredible ability to see and sponge—there was a genius in that. The ability to create out of everything that's flying around. To synthesize it. To put it in words and music.”

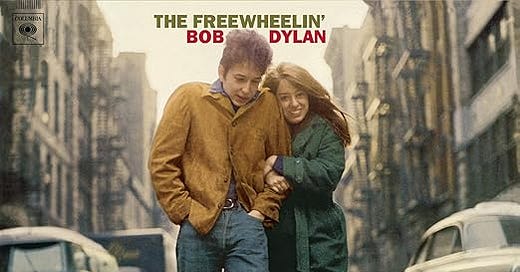

That’s his girlfriend Suze Rotolo, pictured with him on the album cover, writing about him many years later in A Freewheelin’ Time. She’s spent her life being asked about Bob Dylan,13 which brings up the problem with using musicians to explore fame.

Bob Dylan—like Woody Guthrie, and Robert Johnson—certainly has mystique, but it’s a shame that movies chase mystique. Yes, a biopic of a famous person is going to put more butts in seats, and I guess it’s easier to write the script since one can simply change the names from the last musical biopic script exploring the price we pay for fame, but Suze Rotolo, Pete Seeger, Paul Clayton, or Skip James have lives which have more dramatic elements, complex shifts, and thematic questions.14

Freewheelin’ was a success and launched Bob Dylan toward icon status. He followed it up with The Times They Are A-Changing, created through a similar process and in my opinion an even better record. One positive effect of Johnson was that his terseness seemed a healthy check on Dylan’s verbosity. As Dylan turned electric he went back to Woody Guthrie and the folk music tradition of longer and longer songs. He layered in the prose gush of Bound for Glory—Guthrie’s memoir which Dylan probably had memorized—the beatnik poetry and prose like Ginsberg’s Howl, and the unfortunate influence of Rimbaud, for whom Rotolo apparently must answer.

He was hired by the Newport Folk Festival in 1965 as a closing act as shown in A Complete Unknown. He could have said no, but instead he went—which surely helped ticket sales so they were probably pleased—and used the festival as a platform to publicize the next stage of his career. He even chose songs like “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue” to metaphorically describe his break-up with the folk scene while he was breaking up with the folk scene.

Dylan (or Johnson) couldn’t have developed their style of songwriting without self-discipline and patience. Dylan learned hundreds of songs before he wrote any, played hundreds of gigs, and was a responsible, sober, and hard-working professional, even in high school apparently. His luck was to live when gigs were easy to get and a body of traditional song material largely untapped; his talent was his skill at learning songs; his genius was to realize he could apply something someone else did to something he was doing; his success came when he listened and thought about Robert Johnson.

Thanks for reading this very long post! I thought about cutting it but then Bob Dylan never cut anything, why should I?

Next week we’ll return to prehistoric global warming.

Thanks for reading Blame Cannon! For the next couple of months I’ll circle between a series on global warming in prehistory, a story about coal, and a series of true stories about departures and goodbyes.

Please subscribe and share!

Comments are welcome but please no personal insults or profanity.

Here’s a clip from the movie of Dylan and Seeger playing at a party.

Apparently. I wasn’t there of course.

It was part of a series of cassettes James’ older brother made for him with blues and rockabilly.

Later it was renamed Huntington’s Disease but the name change didn’t change how horrible it is. It’s genetic and incurable. Two of Guthrie’s children inherited it and died by the age of 41.

Other folk singers did the same before Dylan, including Ramblin’ Jack Eliot, whose imitation of Woody Guthrie, according to Chronicles, formed part of Dylan’s imitation of Woody Guthrie. Woody’s own persona owed a lot to Will Rogers, a popular vaudeville performer who told jokes while doing rope tricks.

Like A Complete Unknown Dylan did visit Woody Guthrie in the hospital but Woody wasn’t yet mute, and this was a couple months after his arrival, not the night of. Dave Van Ronk and a table of folksingers are pictured briefly in a diner, but Dylan barely interacts with them.

At some point Dylan met Pete Seeger but unlike the movie they were never close friends, Dylan never stayed in Seeger’s house, and Seeger wasn’t that involved in the Greenwich Village scene by the 1960s. He lived upstate and toured mostly. Dylan did hang out with folksinger Mike Seeger, Pete’s half-brother. Also unlike the movie Joan Baez was not much in the Greenwich Village scene; she was based more in the Boston area.

Dylan had made another trip to Charlottesville with Clayton and with Joan Baez, featuring another gig at our own Gaslight, and a visit to the folk collection in Alderman Library. Here’s an account of both Paul Clayton trips.

There’s a wonderful album called Roots of Robert Johnson that shows a lot of these relationships, and I think I have it in the attic, but for this post I’ve used memory, Wikipedia, etc.

Also, while Leroy Carr records were popular, Skip James’ were not, meaning that Robert Johnson was learning from obscure records. Robert Johnson might be the first major American musician who learned mostly from records. His contemporary Woody Guthrie learned his songs overwhelming from playing with other musicians face to face. Son House and Willie Brown seem mostly to have learned face to face as well.

Woody Guthrie used existing tunes almost always in his songs. “This Land is Your Land” is based on the Carter Family tune “When the World’s On Fire,” but is thematically unrelated to it. “Blowin’ in the Wind” is clearly knowingly inspired by its source.

"Stones In My Passway", "32-20 Blues", and "Hellhound On My Trail"

A Complete Unknown has a version of her renamed and stripped of all specificity.

The Coen Brothers’ Inside Llewellyn Davies borrows a title a lot of plot points from Dave Van Ronk. It has several great vignettes but it’s a fairly soulless work, as they seem to admit with their insertion of the gag cat from Blake Snyder’s screenwriting how-to. The Coens handled music far better in O Brother, Where Art Thou? Unfortunately, George Clooney’s performance hasn’t aged well. Why did we think he was a good actor?